One way I start my Advanced Precalculus classes is by having them thinking about n-dimensional cubes. We get there by first exploring the “Painted Block Problem“.

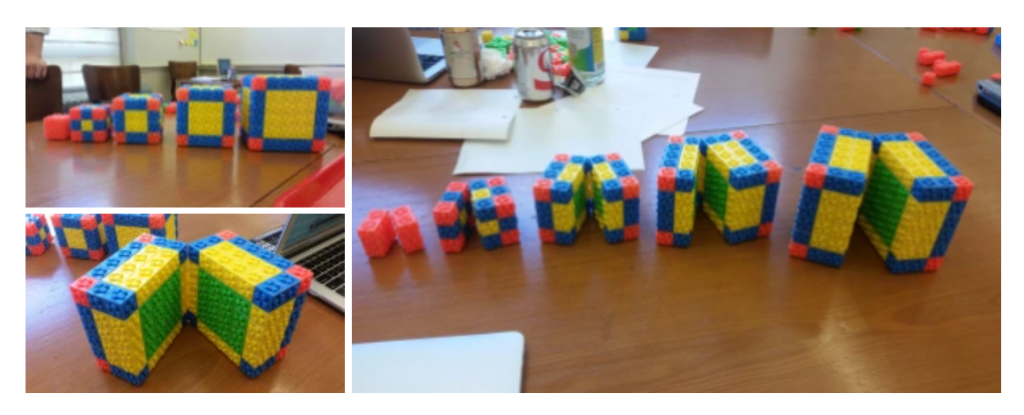

First I have kids look at one of these blocks (I think I give a 5x5x5 block) and have them notice and wonder. Eventually kids wonder what’s on the inside, why different parts are painted different colors, etc. And after some drama, we open up the block, and kids see the new color inside. The question they then are tasked with are how many mini-cubes of each color exist in an n x n x n block.

To be clear, green blocks have 0 exposed faces, yellow have 1 exposed face, blue has 2 exposed faces, and pink has 3 exposed faces.

Something that kids eventually stumble upon as they are working on this problem: in a cube, you have 8 vertices (pink), 12 line segments (blue), 6 faces (yellow), and 1 cube (green).

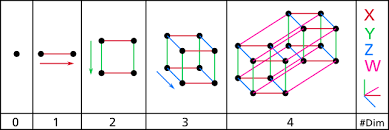

After they solve this problem, I introduce the idea of 0-dimensional cubes (a point), 1-dimensional cubes (a line segment), 2-dimensional cubes (a square), 3-dimensional cubes (a cube), and 4-dimensional cubes (a tesseract)… and how to draw them:

Now let’s look at a 2-dimensional cube (a square). We can see it’s made up of 4 points (0-dimensional cubes), 4 line segments (1-dimensional cubes), and 1 square (2-dimensional cube).

This snip from Wikipedia shows that fact, along with how many smaller dimensional cubes make up a higher dimensional cube.

Finally, here are three questions that I think are fun to ponder:

First, if you look at this chart, there is a really striking pattern…

If you take any number in the chart, double it, and add the number to the left of the number, you’ll get the number in the row below.

The question I ask my kids to answer: why?

Second, without thinking in this recursive way, can you come up with an explicit formula for how many k-dimensional cubes are in a d-dimensional cube? (So if k=1 and d=4, you should get 32.)

(I have only asked my kids this question once, but we had tons of scaffolding. I remember giving it to them the year I devised and solved the problem, and I wanted my kids to have the same gargantuan a-hah moment I had… A couple groups got it, but I realized looking back that the class time we needed to spend on it wasn’t worth the payoff.)

Third, if you add up all the numbers in a row of the chart, you see powers of three. WHAT?!?! ZOMG! Why!?!