In Algebra II, we have been talking about inverses, and compositions. We finally got to the point where we are asking:

what is and what is

?

Last year, to illustrate that both equaled , I showed them a bunch of examples, and I pretty much said… by the property of it working out for a bunch of different examples… that it was true. However, that sort of hand-waving explanation didn’t sit well with me. Not that there are times when handwaving isn’t appropriate, but this was something that they should get. If they truly understand inverse functions, they really should understand why both compositions above should equal

.

So today in class, we started reviewed what we’ve covered about inverses… I told them it’s a “reversal”… you’re swapping every point of a function with

. That reversal graphically looks like a reflection over the line

. Of course, that makes sense, because we’re replacing every

with an

— and that’s the equation that does that. My kids get all this. Which is great. They even get, to some degree, that the domains and ranges of functions and their inverses get swapped because of this.

But then when I say:

“

means you plug in

and you get out

… but then when you plug that new

into your

you’ll be getting

out again”

their eyes glaze over and I sense fear.

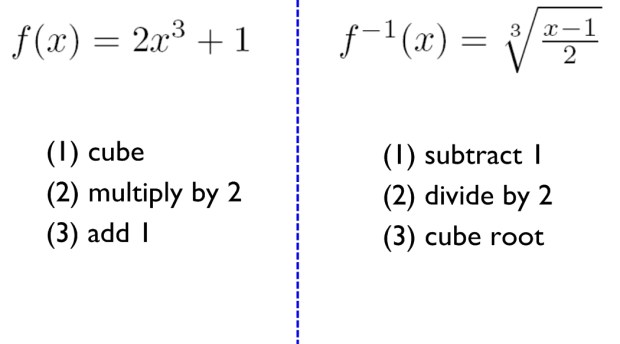

So I came up with this really great way to illustrate exactly what inverses are and how the work… on the ground. I put up the following slide and we talked about what actually we were doing when we inputted an value into both the function and the inverse:

We came up with this:

We then talked about how we noticed that the two sides were “opposites.” Add 1, subtract 1. Multiply by 2, divide by 2. Cube, cube root. And, importantly, that they were in the opposite order.

Then we calculated :

Starting with the inner function:

(1) cube: 27

(2) multiply by 2: 54

(3) add 1: 55

Then we plugged that into the outer function:

(1) subtract 1: 54

(2) divide by 2: 27

(3) cube root: 3

This way, the students could actually see how a composition of a function and its inverse actually gives you the original input back. They could see how each step in the function was undone by the inverse function.

I don’t know… maybe this is common to how y’all teach it. But it was such a revelation for me! I loved teaching it this way because the concept became concrete.[1]

[1] I remember reading some blog some months ago that was talking about solving equations, and how each step in an attempt to get alone was like unwrapping a present. I like that analogy, even though the particular post and blog eludes me. But in those terms, this is like wrapping a present, and then unwrapping it!