Recently, I posted a bit asking people how they introduce integrals. And I got a ton of different responses, which was wonderful. I am going to copy a few bits of comments here, but I really recommend that if you teach calculus, you take a moment to read them all in their entirety.

David P.: I sometimes use the physics of displacement/velocity/acceleration to introduce antiderivatives. […] I am only in my 3rd year teaching, so I’ve not found a “best” way yet. I really like the “surprise” of the FTC that areas and slopes seem like they should have no connection whatsoever, but that they’re almost as related at + and -. So, sometimes I even just say, “ok, we’re done with that section, let’s move on to something else” and then try to surprise them when we get to the connection.

Andy: I usually teach anti-derivatives as part of my derivatives unit. […] I also show how it applies to the position, velocity, acceleration problems. Then I transition to my integration unit. I don’t even tell them about integration and anti-differentiation being related. I just talk about area and then when we get the the fundamental theorem, I am able to drop the crazy idea on them that integration and differentiation are related. I enjoy their reactions to that.

Nick H.: Generally, I like the ask questions first teach skills later approach.

TwoPi: I usually start off with velocity examples, and in each case link the displacement calculation (or approximation) to the geometry of computing the area under the graph of velocity versus time. So start with constant velocity, then linear velocity (and sometimes nice quick applications involving stopping distances for cars at various initial velocities).

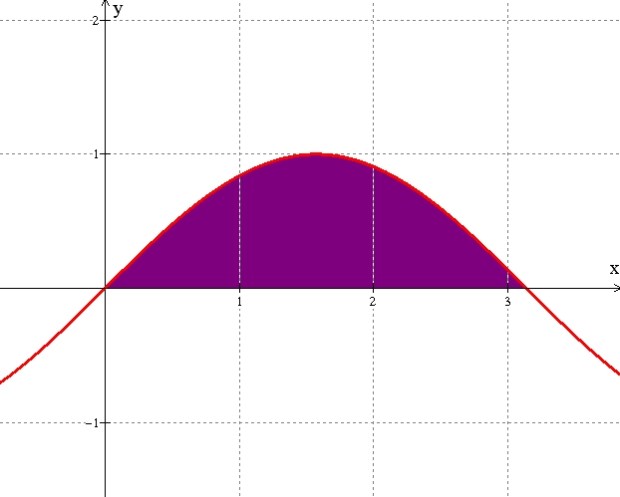

This year I focused on anti-derivatives. On the first day, I just said: the derivative of is

, so the antiderivative of

is

. That’s all. The rest of the class had students struggle through finding simple antiderivatives (PDF and PDF). On the second day, I gave students a method to solving antiderivatives, a method which builds their intuition (PDF). And on the third day, I had students just practice, practice, practice.

Then I gave them a quiz — 17 questions asking for the antiderivatives of functions from to

to

. Moreover, I didn’t give partial credit. If a negative sign was missing, or a constant was incorrect, I took off full credit for the problem.

The average grade for both sections was an A-.

So I have to say that my approach this year worked. I’ll deal with -substitution and all that nonsense later. But the fact is, my students will be able to soon integrate some pretty hard stuff without resorting to

-substitution.

Many of the comments talked about working with position, velocity, and acceleration graphs to start out. I think after I teach the area under curves and Riemann sums, I will go into this topic. Honestly, I was hesitant to start integration with position/velocity/acceleration because anything physics related tends to make my students convulse. They are scared of physics. I wanted to make sure that they didn’t shut down completely before we even start.

(However, I am excited to derive from first principles. I hope to hear lots of oohs and aahs.)