A short while ago, I attended the Teaching Contemporary Mathematics conference at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics (NCSSM). Before leaving for the conference, I had just started related rates with my kids in calculus. I have had a problem with related rates — because the problems are so bad. It’s just one of those places where you feel: this is where calculus should come alive.

But it doesn’t.

Well, at the conference, one of the last lectures I attended was given by Maria Hernandez. The lecture was ostensibly on using video in the precalculus and calculus curriculum. But in actuality, it was a solution to my related rates problem. Maria had created a wonderful, short activity which brings to life — visually — the idea of related rates.

I stole it, slightly modified it, and used it in my classroom the day after I got back. The activity’s best quality is that students could see math in action, not only from the use of the video, but also from the graphs they produced from analyzing the video. We’d been spending months on this “take the derivative” “take the derivative” “take the derivative” that I felt like we were losing all the understanding we had built up for abstraction. It was perfect to bring us back to basics. I enjoyed doing this in the classroom, and so I asked her if I could share it here. She generously replied:

Of course you can write about the video projects on your blog and feel free to share the worksheets. You can add my e-mail address so folks can send me a note if they have questions.

Maria’s email is: hernandez at ncssm dot edu

Things to note:

1. All my kids have school issued laptops with Logger Pro installed. (I’ve also heard very good things about the free program Tracker which does the same things as Logger Pro.)

2. All my kids used Logger Pro in other classes, and although most weren’t experts at it, it wasn’t completely new to them either

3. This is all Maria Hernandez’s work… I am just sharing it and my experience with it in my classroom. But if you love it, send her an email shout out!

Prelude

You teach the basics of related rates, in the same, boring way you always do. Blow up a balloon, and ask what sorts of things are changing as the balloon blows up. (Volume, surface area, circumference if you assume it’s a sphere, tension in the rubber, etc.). Then you start talking about how these things are all connected — if you have a bigger volume, you have a bigger surface area — and as one changes, the other changes too. And related rates are how these things are changing in relation to each other.

Go through some basic problems together. I use this packet of problems — where we do some together as a class, some they work with a partner, and some they do on their own. In general, I don’t do the harder related rates problems, because for my (non AP) class, I care more about them getting the fundamental ideas.

The Video

Now it’s time to show the kids The Video.

[Maria has put the video up for you to download here.]

Play them the video once, then ask them to jot down things that are changing in time while you play it again. They will come up with things like radius of the cone, the volume of the cone, the height of the cone, the surface area of the cone, the amount of water that is being poured out of the beaker, the angle of the beaker, etc.

The Question

Here’s the question you should pose: “The person who tried to pour the water into the glass tried really really really really hard to pour it at a constant rate. Watch the video again. Do you think he did a good job?”

So play the video again, and then when they’re done, pose another question:

“How does the rate of change of the volume of water being poured from the beaker relate to the rate of change of the volume of the cone?”

[Note: I’m glad I anticipated this. Interestingly, it wasn’t totally obvious for my kids why the two rates of change would be the same.]

The Task

So then you let them know their task. They’re going to be using related rates to check to see if the person pouring the water did a good job pouring it at a constant rate. To do this, they’re going to use (a) a guided worksheet and (b) Logger Pro.

Set them off on the guided worksheet. Maria’s original guided worksheet (with Logger Pro instructions!) is here. My (very slightly modified) worksheet is here:

Let them at it however you want. In one class, I had them work on Section A and then we had a discussion about their results. In another, I let them move onto Section B without discussing their results until the end. You can figure out what will be best for you.

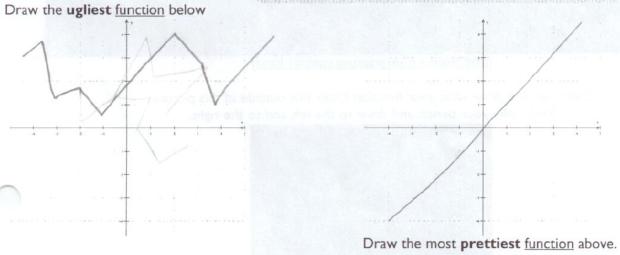

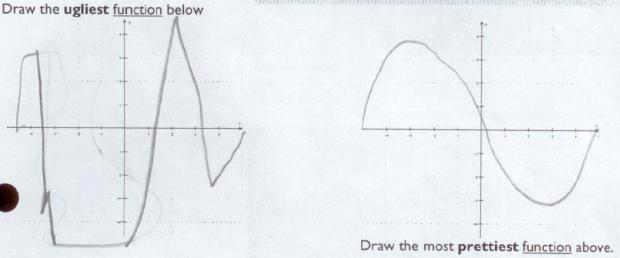

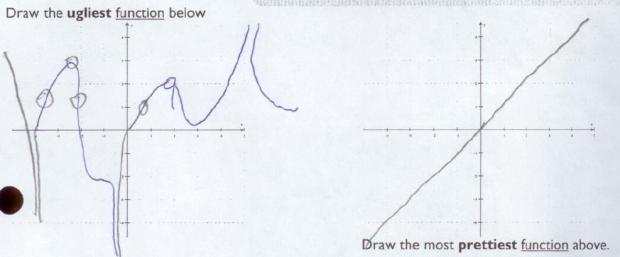

The general idea behind the worksheet is that students make predictions, and then use Logger Pro to evaluate their predictions. First, students capture data using Logger Pro…

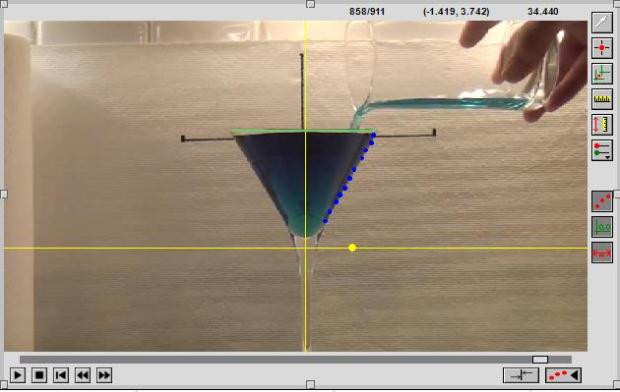

The yellow lines are our coordinate axes (the origin being at the “bottom” of the cone). The dots give us something special. As we play the movie, frame by frame, we add these dots at various times showing where the water is at these times. Notice the wonderful thing about recording the dots on the edge of the class… the x-coordinate of these dots represents the radius of the cone, and the y-coordinate represents the height of the cone.

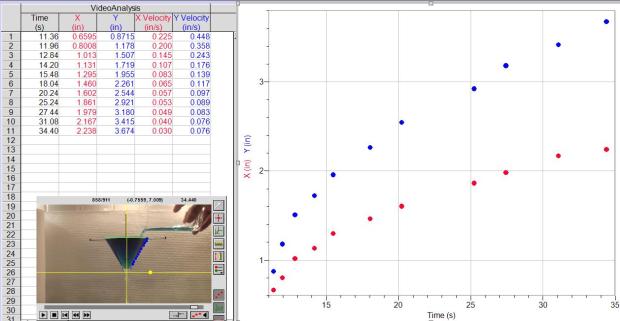

Once the movie has been marked up with blue dots, students can see what wonderful things Logger Pro gives them!

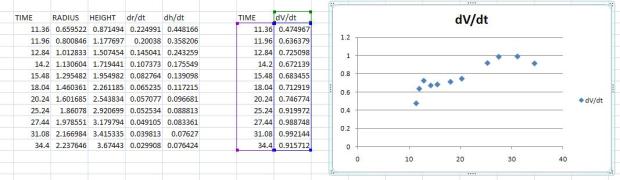

Not only does Logger Pro make a graph of radius v. time and height v. time (lovely!), but it also gives us a spreadsheet set of data… at each time that we made a dot, we are given the radius, the height, and for free thanks to Logger Pro, and

.

Awesome! Well using the fact that , we can conclude that:

.

Oh, how nice. Logger Pro gives us all our unknowns in that spreadsheet so we can calculate . And isn’t that what we cared to find out? If

was changing at a constant rate?

Some things of note:

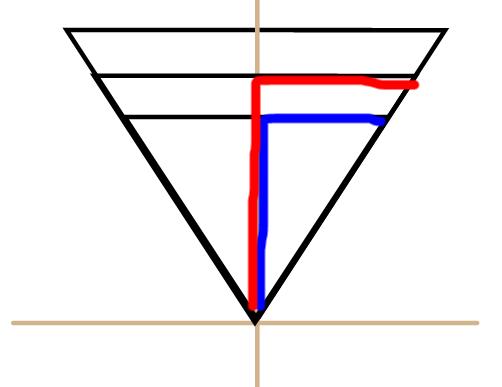

1. When discussing Section A, you can have a very nice discussion about your students’ predictions. It was cool to discuss why the general shape of r vs. t and h vs. t should be very close to each other. In fact, if you draw the cone filled in at different heights, you can use similar triangles to argue that however fast r is changing, h must be changing at a proportional rate. Why? Similar triangles!

2. In one class, I gave my kids class time to work on the Logger Pro part of the activity. In my other class, I had them work on Logger Pro at home. It was clear to me that the class who worked on Logger Pro in class enjoyed the activity more. There was more discussion, and they had people to talk to when they had technical difficulties. The class that had to do Logger Pro at home was not super pleased by it!

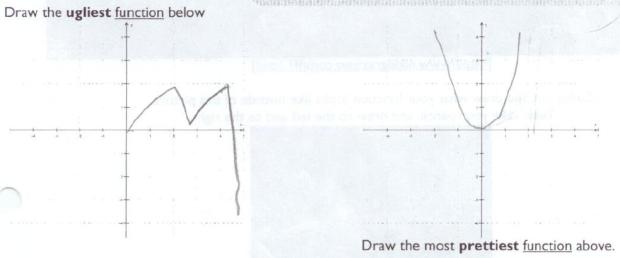

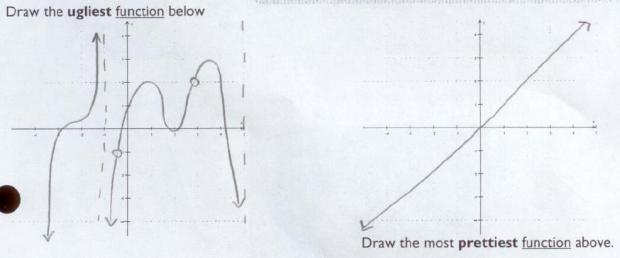

The Conclusion

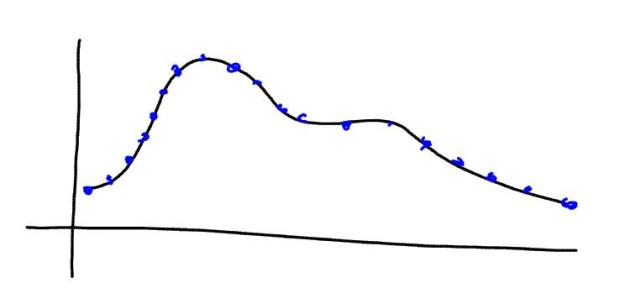

My kids used the guided worksheet to calculate at a bunch of different times, and to graph

v. time. It turns out (we used Excel) we get something that looks like:

My kids all conclude that the person pouring the water doesn’t do a good job.

I’m not quite done yet, though. I ask them one last question… If the graph for v. time looked like:

“this would mean that the guy was pouring at a constant rate… because the data almost fits a line.”

“this would mean that the guy was pouring at a constant rate… because the data almost fits a line.”

I tricked almost all my kids in both of my classes, when I said it like that… But one kid in each class caught on that I was faking them out. And they said that this doesn’t mean the water was being poured at a constant rate… but that more and more water was being poured out over time. The only way we would be assured that the water was being poured out at a constant rate is if our data fit a horizontal line…

Nice.

Extensions

I’ve been thinking… perhaps in the fourth quarter I am going to have my students make their own videos filling up cylinders and cones. In a group of 3, I was thinking of asking them to make 2 videos:

- trying to pour the water in at a constant rate

- trying to pour the water in in such a way that the graph of

v. time has a special shape I give them (a decreasing line? a bell curve-y shape?)

Basically it’s going to be a challenge for them, and I’ll have some sort of prize for the group that can get the water in at the most constant rate, and a prize for the group that can get the water to pour in the special shape I give them. Of course the bonus for me is that I might get some more videos to use in future years…