I was reading — as I think we all were — that New York Times article “Building a Better Teacher.” In that article, a number of ideas and sentences and thoughts leaped out at me, especially concerning Doug Lemov’s taxonomy. (Yes, like you, I’ve already pre-ordered the book and cannot wait for it to arrive.) One of Doug’s points is:

The J-Factor, No. 46, is a list of ways to inject a classroom with joy, from giving students nicknames to handing out vocabulary words in sealed envelopes to build suspense.

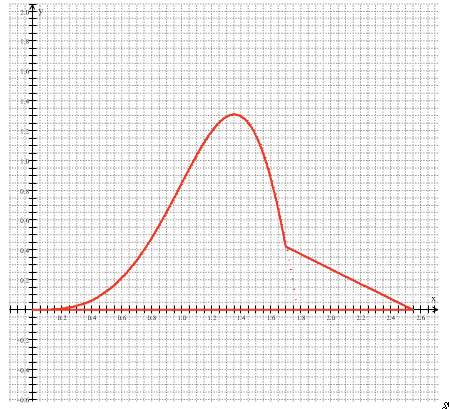

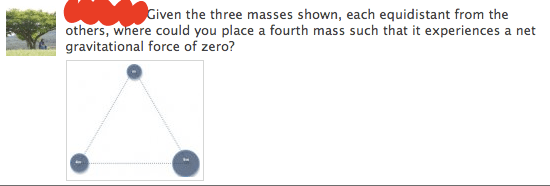

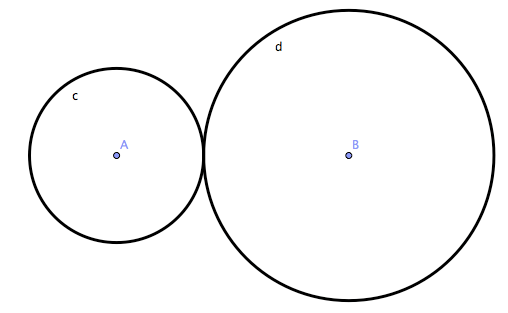

I love the idea of sealing things up and unveiling them. So in my calculus class, right after we finished anti-derivatives but before we embarked on integrals, I gave my kids 15 or 20 minutes and this picture.

I showed them a Chinese take out container which I shook (and it rattled), and I said it had very special prizes inside. I showed them a fancy envelope and gave them each a notecard that they would place in the envelope. With their name, and their area estimate.

Each kid worked individually — using anything they had on them like rulers, straightedges, calculators. One student asked if he could use a scale from the physics lab (I said no, mainly because of the time issue.) I did this in two classes. Both seemed into it, but one was definitely more into it than the other.

What was interesting to me was how hard it was for them. Not the estimating, or the making of triangles and rectangles and other smaller pieces. What was hard for them was being asked to do something that they didn’t know how to do. It happened multiple times that kids were sheepishly telling me that they didn’t know how to start (they had already drawn auxiliary lines and broke the figure up into smaller pieces — um… you DID start, darlin’), that they were doing it wrong (um, didn’t I say there was no wrong way to do this?), that they didn’t know the right way (um, see my last um). They were telling me this to assuage some part of their psyche that was telling them that they had to be right. I told them to STOP BEING CONCERNED ABOUT KNOWING THE RIGHT WAY and just TRY SOMETHING! Then they did.

I also mentioned that last year someone got the answer right to TWO decimal places — setting the bar high.[1]

At the end of the allotted time, I collected the notecards, put them in the envelope, and sealed it with a flourish.

I told them it would take a week or so before we could unveil the envelope (“but Mr. Shaaaaaaaaaaah”) and find out who came the closest to the real answer. And how would we find the real answer?

Calculus.

This was their hook for integrals. The next day (today) I introduced the idea of area under the curve being related to that anti-derivative thingamajig that they had been working on. I got at least 4 questions whining about needing to know who got the closest answer. I stoically responded “you’re going to find out when you figure out the true answer… soon.” The hook worked, and the bait is waiting to be won. For them, the bait is getting the surprise inside that dang Chinese take out box. For me, well, they are now curious.

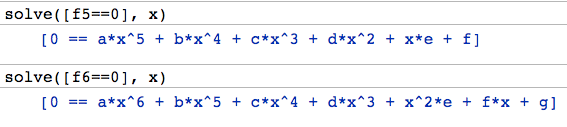

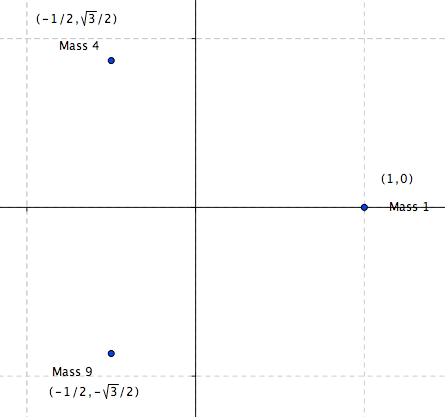

[1] That was technically true, but slightly a lie. The exercise we did last year was different. I gave various pairs of students the same graph with different gridlines… and I had them estimate. So, for example, one pair of students got:

So clearly their estimation was going to be better — and it is unsurprising they could get an estimation to 2 decimal places. And last year we talked about how the more gridlines you have, the better your estimate can be.