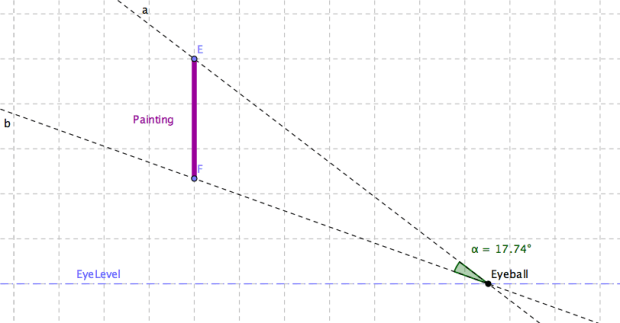

In my most recent calculus classes, I wanted to show my kids their first “not nice” functions. After being introduced to how to find limits graphically (fancy way of saying: looking at the graph of a function) and numerically (fancy way of saying: using the graphing calculator’s TABLE function to guesstimate limits), I wanted to have them think about what they learned.

I had time to show one class that these methods aren’t foolproof — that the calculator can lie to you, and make you think a limit is 3 when it is in fact 3.004, or that it can’t graph things when numbers get too large or too small. So they have to be careful. And that we will be learning algebraic methods to do limits. But for now, they need to use their brains and wits.

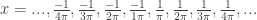

So I divided them into groups of 2 and 3 and had them use whatever methods they wanted to find:

I made them each draw a sketch of the function, write down an appropriate table of values, make observations about the function, and then decide on an answer. (In one class, I had each group turn in their findings, and then I photocopied them and distributed them and had the class talk collectively about the results the next day. In the other class, we didn’t have time for this, and we just met up together as a group to talk.)

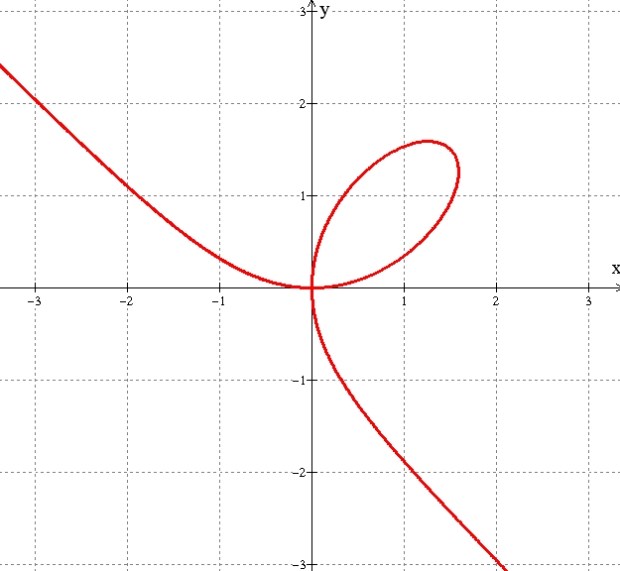

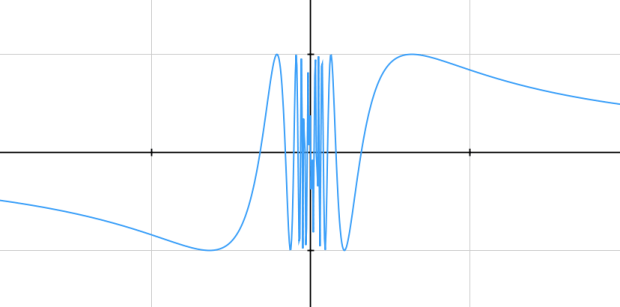

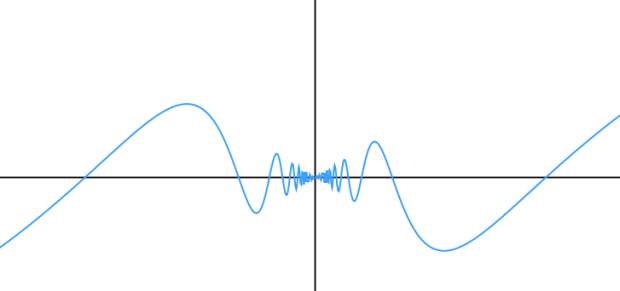

FYI, the graph is here.

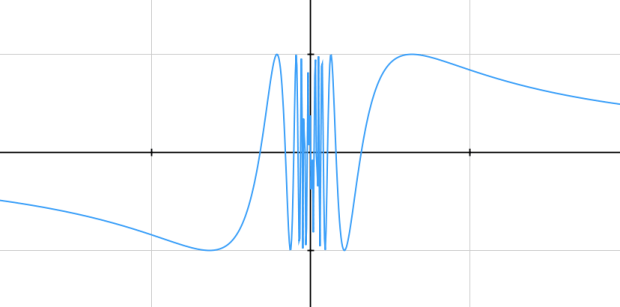

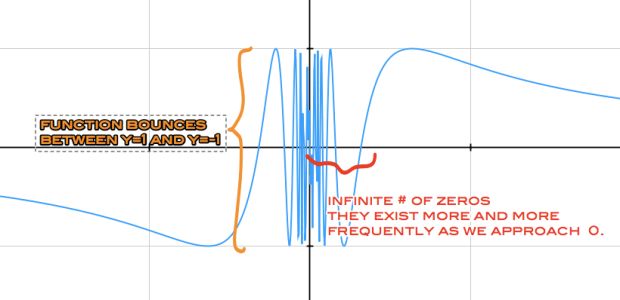

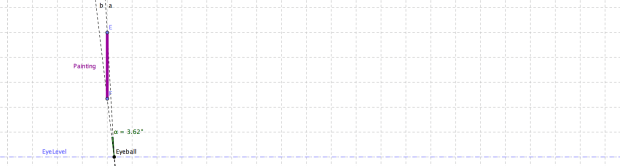

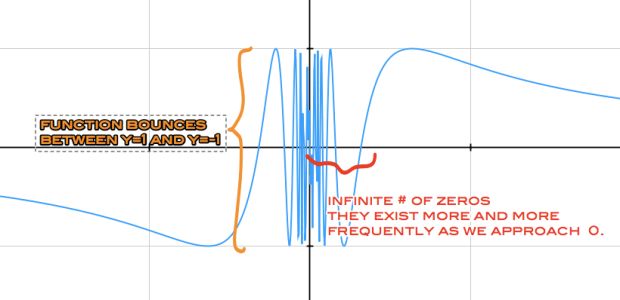

It was great. Students were debating whether the craziness was a function of the calculator lying or if that actually was what the function looked like. They wondered if the limit was 0 or if it was “does not exist.” They noticed that the function starts to oscillate more and more rapidly as  approaches 0. They noticed that it bounced between -1 and 1. It’s not an easy question to solve with this information.

approaches 0. They noticed that it bounced between -1 and 1. It’s not an easy question to solve with this information.

When we came back as a group, we talked about their observations and conclusions, and documented them on the board — so everyone had the same notes. Then I said: “so… one of you said that the function is crossing the  axis more and more as

axis more and more as  is getting closer and closer to 0. Can we be more exact? Where does the function cross the

is getting closer and closer to 0. Can we be more exact? Where does the function cross the  axis?”

axis?”

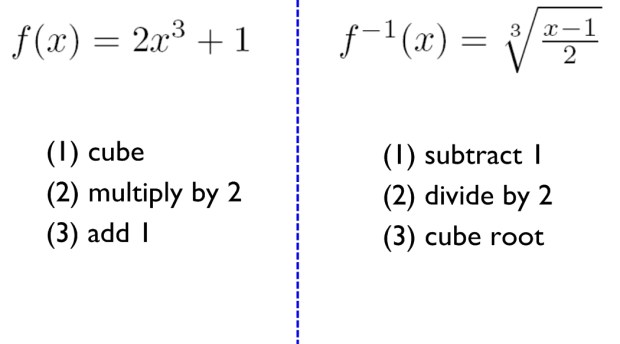

Of course my students didn’t know exactly what to do. We got to the point where we knew we had to solve:

But then they were stuck. So I guided them through it.

I asked: “When is

We generated:

We then said:

We went through solving one of the equations for  and saw that we needed the reciprocals…

and saw that we needed the reciprocals…

We concluded:

I then asked: So what? Why did we do this? Don’t lose the forest for the trees…

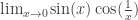

Finally, we converted those numbers to decimal approximations

and saw that the zeros were getting more and more frequent as we approached 0. No matter how close we came to zero, we were still going to be bobbing up and down on the function. And crucially, we’ll be bobbing up and down between  to

to  .

.

We then talked about what a limit means again… what the  value of a function is approaching as the

value of a function is approaching as the  value gets closer and closer to a number. Using that informal definition, I asked them if the

value gets closer and closer to a number. Using that informal definition, I asked them if the  value of the function was approaching some number as

value of the function was approaching some number as  was approaching 0.

was approaching 0.

At this point, most of my kids had that “a hah” moment.

I am definitely doing this again next year, but perhaps more formalized. I might generate a list of good conceptual questions to walk them through this more systematically. One such question: “How many zeros are there in the interval (.5,1)? How about (.1,1)? How about (.01,1)? How about (.001,.1)? How about (0.0001,1)? And finally, how about (0,1)?” Another such question: “How do we know the function will bounce between  and

and  ?”

?”

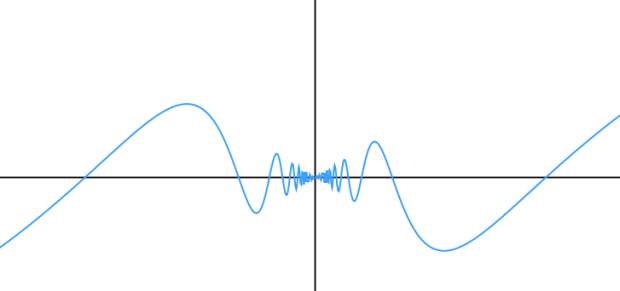

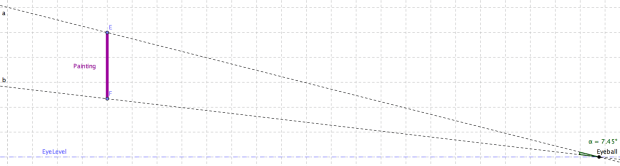

Also, maybe next year, I’ll couple it with an analysis of the function:

The function behaves similarly (crosses the  axis more and more rapidly as

axis more and more rapidly as  approaches 0), but the limit in this case is 0. You can see it in the graph easiest.

approaches 0), but the limit in this case is 0. You can see it in the graph easiest.

So if anyone out there is looking for something to spice limits up, you might want to really go in depth into these functions. They are often used as exemplars, but rarely investigated.

and