So I’m a teacher that usually overprepares. I have my lesson set up beforehand. Very little is set up for “free form.” This is even true for my Multivariable Calculus class of 5 students.

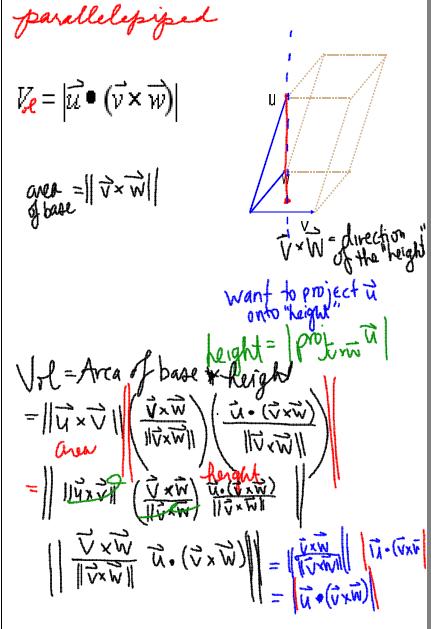

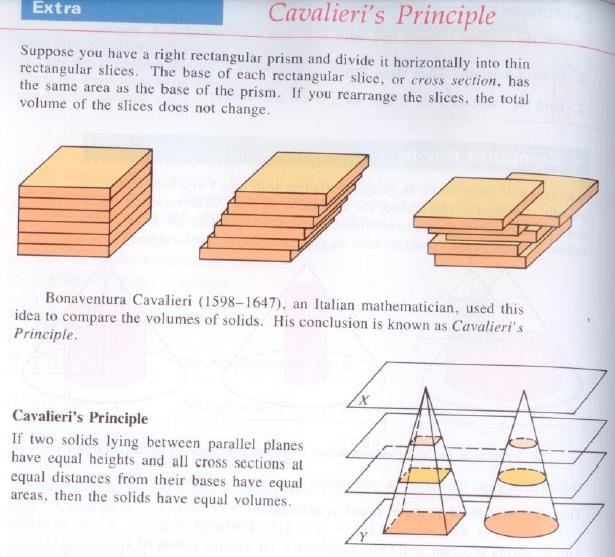

To be fair, though, in that class we do generally take a 20 minute tangent here or there. Like today we were resolving the acceleration vector of a vector valued function into normal and tangental components — and we spent 15 minutes deriving them because I just decided we should. Spur of the moment thing. Or a few weeks ago, I gave my student 50 minutes to come up with how to convert between rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinates, with no help. But generally, the lessons are carefully planned out. Here’s an example of my introduction to triple integrals (which we do way later in the year) so you can get a sense:

slideshare id=1597835&doc=mvcalculustripleintegrals-090617102556-phpapp01

A few days ago, we had gone over the homework and somehow got on the topic of us being on the earth. I honestly can’t remember what prompted it. But we started talking about the force of gravity, which we feel because the earth is so massive. Then I had an insight — a direction we could take the conversation.

We are also spinning: “Does that change anything?”

I stopped class. I paused for 15 seconds, told the students to hush while I considered whether to go down this route. I felt this pang of deviating from my preplanned lesson. We were going to be behind. Do I really want to possibly come to a dead end?

I almost pushed it off. I was going to “leave it as an exercise to the reader” — tell my students they could think about it independently. But just as I was about to brush it off, I thought: WTFrak. Tangents are more interesting and more memorable, when the kids are interested in them.

My kids seemed interested.

So I threw away the lesson I had planned completely, and we went off the cuff, without a known destination in sight.

So back to the spinning earth. I didn’t know. I hadn’t thought about that kinda obvious fact before — we’re spinning, so that should have some consequences

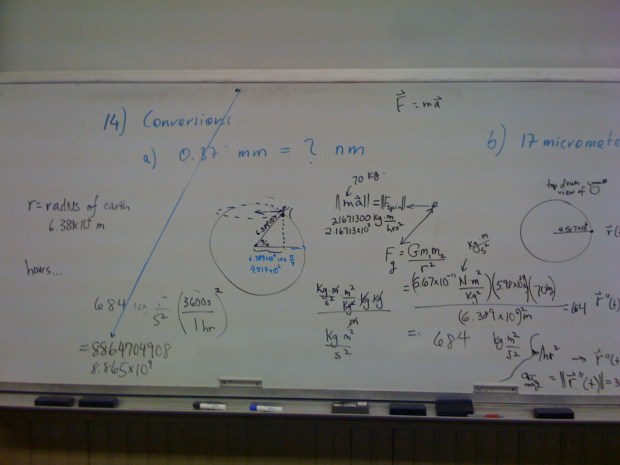

We learned in our previous class that if something is spinning at a constant velocity in a circular motion, it must have an acceleration pointing inward to the center of the circle. So since we are spinning, once around our latitude every day, we must also feel a force pulling us to the center of the circle.

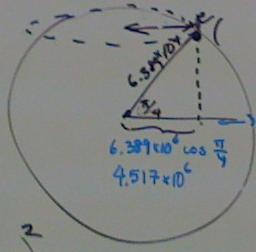

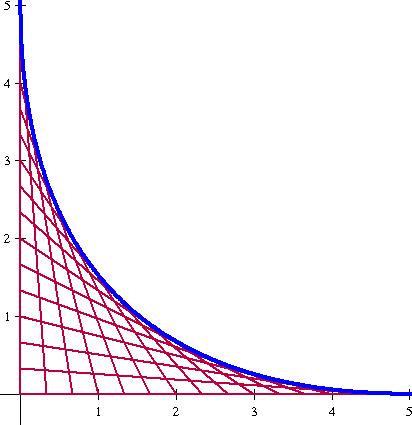

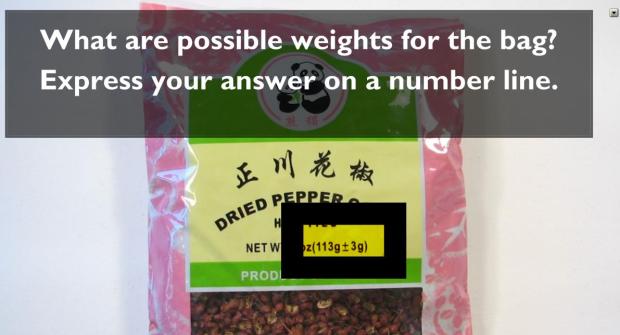

If we model the earth as a sphere, not tilted, and put us at an angle 45 degrees from the equator… we feel a force pulling us to the center of the earth (from gravity), and also a force pulling us directly inwards (centripetal – from rotating) :

But I don’t feel that centripetal force. I jump up, I come down. I don’t feel like I’m being pulled in any other direction.

So we decided to calculate the magnitude of the two forces, and figure out what’s going on.

Awesome.

I left giddy. We figured that the centripetal force was about 1/400 the force of gravity. Afterwards, I did a few more calculations, and realized that actually some of this centripetal force will be in the direction of gravity, so it will feel even less powerful.

I’m leaving for a wedding tomorrow, so I’m having my kids do a formal writeup of what they found. I can’t wait to see it. I am going to show it to their AP Physics teacher.

(As an aside, I think I’ve found the physics term for what we discovered: the Coriolis force. If anyone knows anything about it, or any good resources on it, let me know!)