I was so enthralled with Judge Sand’s city of Yonkers case that I couldn’t help but do a little more research on him. And lo and behold, nary a page in from a google search, I found another case that deals with math!

The setup

Henry Barschall, working for the American Physical Society and the American Institute of Physics, investigated the cost of science journal subscriptions for libraries. Even then in 1986 (as we hear is still the case now), science journals were increasing their prices — for a variety of reasons. And science journals were on average more expensive than journals in other disciplines (e.g. in 1985, the average yearly subscription for a science journal was $328, while for philosophy, it was only $47 — here).

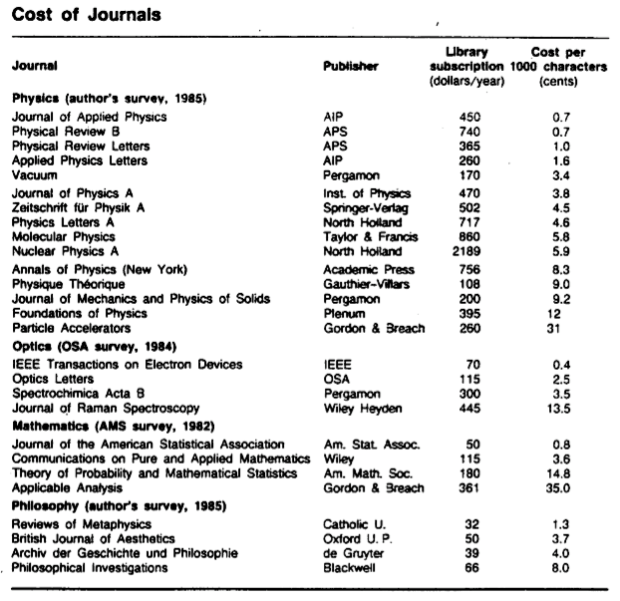

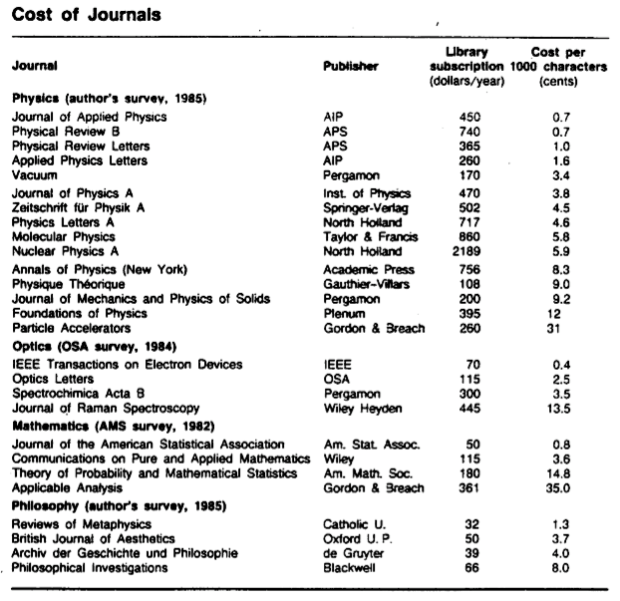

The survey was done and ready to be published in Physics Today. Barschall outlined his methodology here. The intial results which were published in 1986 are below:

Note that for the physics journals, the American Physical Society and the American Institute of Physics were the most cost effective (0.7 cents/1000 characters), while Gordon and Breach were the least cost effective (31 cents/1000 characters). For this case, it’s important to note who sponsored the study! (The same organizations who came out the “winners.”)

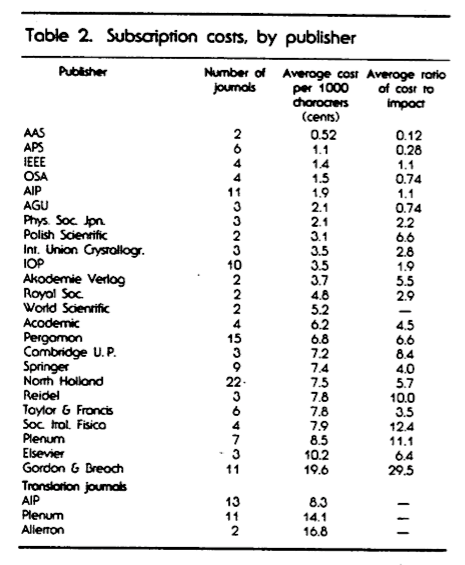

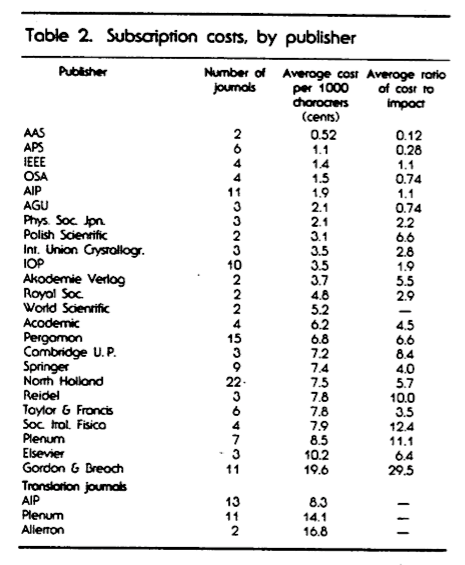

An expanded survey, published in 1988, took into account not only the price, but the “impact” (or importance) of the journal… The metric for the impact was the average number of papers which cited an article in the journal two years after its publication. The more “impact” the journal had, according to the study, the more it mitigated a higher cost (hence: a ratio was created).

Again, APS and AIP were near the top of the list, while Gordon and Breach were way down at the bottom, with a cost/impact ratio more than twice the next publisher.

Gordon and Breach sued the APS and AIP. Judge Leonard Sand heard the case, and summarized it as follows:

This action, a dispute between publishers of scientific journals, raises an issue of first impression: whether a non-profit publisher may be sued for false advertising under the Lanham Act for publishing comparative surveys of scientific journals which, through the employment of a misleading rating system, rate its own publications as superior.

[…]

These articles, G&B alleges, constituted the start of a “continuous promotional campaign” waged by AIP and APS against them with the aid of Barschall’s survey results. First, G&B alleges, AIP and APS distributed “preprints” of the 1988 survey results to librarians (the primary purchasers of scientific journals) at a conference in June 1988. Since that time, G&B alleges, defendants have continued to disseminate the results of Barschall’s surveys to prospective purchasers through press releases, letters to the editor, “electronic mailings,” and meetings with librarians (“secondary uses” of the articles). G&B states that its attempts to reach an accommodation with defendants have been fruitless, and that it has been forced to resort to the courts. After filing a series of legal actions in Europe claiming unfair competition, and failing to receive satisfaction in Swiss, German, and French courts, G&B brought this lawsuit in September 1993.

G&B contends that the articles are promotional materials cloaked in the deceptive guise of “neutral” academic inquiry, and thus constitute misleading advertising under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), and comparable provisions of New York General Business Law. Barschall’s studies, G&B contends, far from being neutral, in fact constitute a “cynical promotional campaign” by AIP and APS to deceive librarians and other consumers of scientific journals into thinking that their journals have been “scientifically” proven to be of superior value.

Judge Sand’s judicial opinions, the trial transcript (really interesting stuff! I swear!), Barchall’s papers, and other related material have been put on this site at Stanford for you to read.

Eventually in 1997 (yes, justice takes a long time to render), Judge Sand made his final ruling:

Barschall’s methodology has been demonstrated to establish reliably precisely the proposition for which defendants cited it — that defendants’ physics journals, as measured by cost per character and by cost per character divided by impact factor, are substantially more cost-effective than those published by plaintiffs. Plaintiffs have proved only the unremarkable proposition that a librarian would be ill-advised to rely on Barschall’s study to the exclusion of all other considerations in making purchasing decisions. This consideration in no way makes Barschall’s study or defendants’ descriptions thereof false, and accordingly judgment is granted to defendants.

And the case is over!

Could this be useful in a math class?

I don’t know. I honestly can’t see myself using it next year, except maybe for a quick classroom discussion — a few “do nows” where each day I introduce more and more of the case and the evidence, and we talk about the math issues it raises…

- Before presenting the data, it could lead to a discussion of how one might measure the cost-effectiveness of journals, and different ways students could imagine calculating them.

- Does Barschall’s method of measuring impact make sense? Does taking a ratio of cost per thousand characters to impact work? Why divide? (That will be hard for my students to get.)

- A baby project: students could go to the school library and get data about various online databases that the library subscribes to, and try to determine whether subscribing is cost-effective for the school. Or at least, the class could try to brainstorm out what sorts of data we would want (e.g. the cost of the database annually, whether — and if so, how quickly — the cost of the database has been increasing, the number of times the databases are accessed each day, the amount of information the databases contain, etc.)But honestly, this seems like it isn’t really worth it. It would make for an interesting independent study, though.

- A discussion about whether the survey was ethical or not, merely by virtue of the fact that those producing it were players in the game (non-profit players, but players none-the-less). [A similar discussion would be whether drug companies should produce their own studies of drug effectiveness.]

- Ideas for how one might present the data visually?

- Should a court (even with scientific experts being called in) be the final arbiter in whether a mathematical study/survey was sound or not? If not, who should be?

But besides being interesting, do you see a good use for it in the classroom? If you do, leave a comment with an idea!

is expressed in the polar form

by making the substitution

and

.

and

as functions of

and

and use implicit differentiation to show that:

and

as functions of

and

and use implicit differentiation to show that:

satisfies Laplace’s equation

satisfies the equation