In my last post, I shared a question posed to me by a student. Essentially, it boiled down to: can we algebraically prove that the following will always be an integer?

I shared it with two friends in my department because they both really love combinatorics like me. One gave me some really nice ways to think about it and set me upon a nice path forward. But before I could go there, the other (the illustrious James Cleveland-Tran) shared with me his thinking. It was amazing. I wrote in my last post I love when things I can’t explain (in mathematics) feel like magic, because it means I get to learn something cool to figure out what makes it work. And when I do, when I understand something so well that the magic suddenly feels mundane (I think I used the word “obvious”), that is a wonderful moment. Because that means I fully grasp something. As James shared his thinking with me, I had that moment. Of course this had to be true. It doesn’t involve anything so deep I had to work to get it. It felt simple, and simply put, beautiful. I’m going to share that reasoning here.

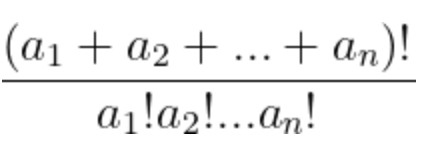

So to start, I want to remind y’all that the things being factorialized and multiplied in the denominator all add up to the numerator. I am going to use a specific example to illustrate this and work through the ideas:

The whole proof hinges on this idea: a product of n consecutive integers will be divisible by n! Since James showed me this, I’ll refer to this as the James’ Theorem.

So let’s look at this example more closely. I’m going to expand out the numerator.

Now I’m going to group the numerator into groups of consecutive integers. Of course you can see we can do this in different ways. Here are some of them!

By James’ Theorem, we know the three consecutive blue numbers in the top of the fraction will evenly divide the 3! in the bottom of the fraction, the four consecutive red numbers in the fraction will evenly divide the 4! in the bottom of the fraction, and the five consecutive yellow numbers will evenly divide the 5! in the bottom of the fraction. And thus we’re done.

Now how do we know James’ Theorem is true?

Okay, I officially hate my life. GOSHDARNIT ALL TO HECK! As I was typing up the rest of this post, showcasing what I thought was a wonderful, deep, clear understanding of something that felt so obvious, I realized I don’t understand it fully. ACK!

And so, again, I’m in the realm of magic again. This isn’t the first time. This happens to me a lot with really interesting problems. I almost always discover a mistake in my reasoning when trying to write up an explanation with simplicity but also being comprehensive. And that’s exactly what happened here. (This is one reason why explaining my reasoning clearly to others is so important in my math process, and why I love kids talking about their mathematical thinking with others! It forces critical self-reflection.)

So here’s where we’re at. I do fully accept that if James’ Theorem is true, then we’re done! But I had a misconception that makes me feel a little embarrassed looking back at things.

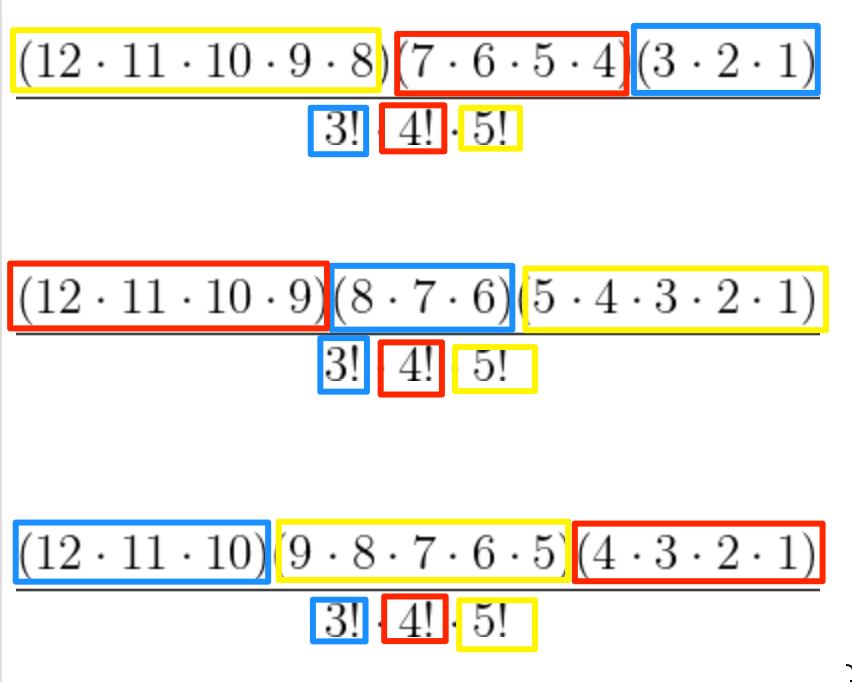

I was thinking for each consecutive 5 integers, for example, had one of those integers divisible by 5, a different one had one of those integers divisible by 4, a different one had one of those integers divisible by 3, a different one had one of those divisible by 2, and the last remaining one had one divisible by 1.

Like I’m illustrating here:

But… yeah… that’s not always the case… Here’s the text I sent my friend James…

I’m now wondering about the factorial proof. I agree that if we know that the product of k consecutive integers were divisible by k!, the proof is done. But it’s not obvious to me anymore.

If we have the five numbers 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, I had convinced myself that one was divisible by 5, a different one was divisible by 4, a different one was divisible by 3, a different one was divisible by 2, and the last one was divisible by one. In my mind they had to be different ones. But that doesn’t work here.

And I thought they had to be different because in this case for example when they’re not, you then have to show after you divide one number out you might have to then divide a second number out and I don’t know why the second division necessarily works. Like in this example… after dividing out the 5 and the 4 and the 3… the 2 would have to divide into the 30 or 28. But the 28 already had 4 divided out so it wouldn’t be able to be divisible by 2 (what you’re left with is 7). And it feels magical that the 30, after being divided out by 5, happens to still then be divisible by 2.

In other words, how do I know the 2 will still be able to be divided into the 30 or 28?!?

Of course, I know with this specific example it can divide into the 30 (even after the 5 divides into the 30)… but how do I know if I did this with another set of n consecutive numbers, I wouldn’t hit a place where after you’ve divided out a bunch of numbers, you’re left with a number in the denominator that won’t go into the numerator?

Here’s my current state of things. I believe James’ Theorem and know it will unlock this problem. But I don’t get with any depth why it’s true. So I’m super happy that the original question posed by my student has been reduced to something “smaller.” I also think I might be at the point of wanting to google this to see what I can discover. I am still going to hold off for a bit longer, but I’m not sure how much longer.

Here is some of my current thinking, delivered via my phone while I wait for s kid to finish soccer, so… might add/revise later. I don’t know.

In a set of five consecutive integers, exactly one of them will be a multiple of 5, as the multiples occur every 5 numbers. Within that set, you will also have at least one multiple of 4, since they occur every four numbers, etc. From there, you will find multiples of every smaller whole number since they will appear at greater frequency.

likewise, in a set of n numbers, you will be able to find one multiple of n and every whole number less than n.

And in a set of 8 consecutive integers, one of them will be divisible by 8, two will be divisible by 4, and three will be divisible by 2. Of those two that are divisible by 4, one of them will already be “used up” by the 8, but it’s okay, because one of them won’t be. Of the three of the numbers that are divisible by 2, two will be also be multiples of 4 and 8, but one of them is only a multiple of 2, so it is used there.

Also also it’s helpful for me to think of this with a color coded version of the sieve of Eratosthenes. Now it’s time for now to go!

I love, love that you and James are talking about this, and love that you posted it. I feel like I still have more to think about and revise.

I wonder if you know the Legendre’s Theorem about the exponent of a prime p in the factorization of the number n!

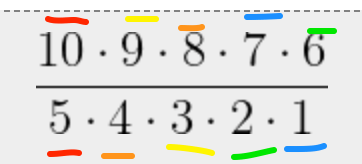

Either case, you could look at your examples in this way:

In $$frac{10cdot9cdot8cdot7cdot6}{5cdot4cdot3cdot2cdot1}$$

Choose any prime number $$pleq 5$$, what is the exponent of p in 5!? What about the factorization of the numerator?

Same with the last example.

Sorry if someone has mentioned this before.