I’m sitting in a building at Exeter, digesting lunch and waiting for the next session to begin. I’m at what has so far been a really valuable math teacher conference. What impresses me most, besides the amazing and neverending supply of food that they offer, is the population of teachers that come. Many of the teachers I’m talking with have 20+ years of experience in the classroom.

Over the next few days I’m going to use this blog to talk about some of the tidbits of interesting problems I’ve been presented with, to good resources or programs that I was introduced to, to neat ways to present topics in class, to ideas that I’ve been inspired to think about.

I’m going to start with a nice calculus problem — probably good for a AP Calculus BC class, but there is definitely a way I could show this problem to my non-AP class.

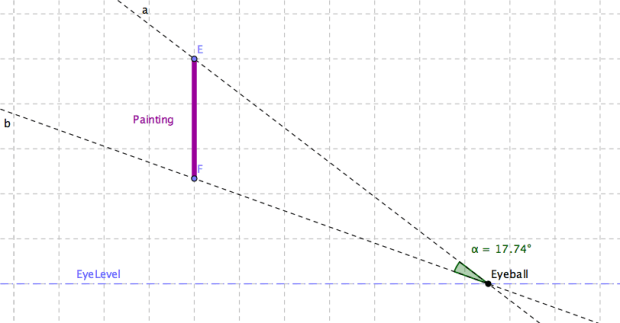

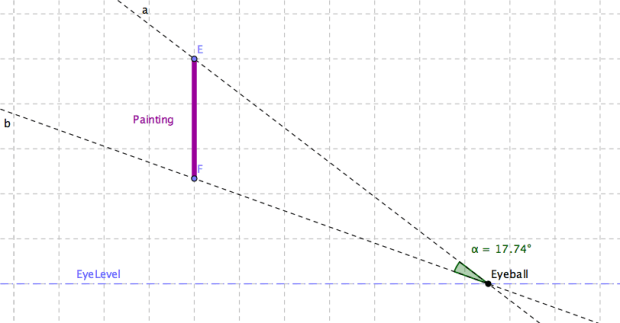

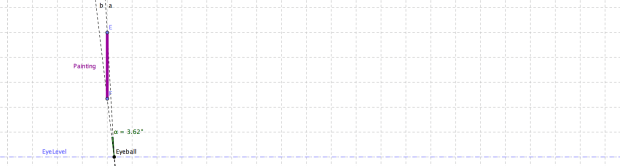

Here’s the problem. You’re in a museum and you’re looking at a painting which is hung above eye level. (There is a specific painting which is hung high in the entrance room at the Brooklyn Museum that I think of with this problem.) You are standing some distance away from it. The question is: what is the largest angle ( ) that you can get as you walk forwards and backwards? (See diagram below for setup.)

) that you can get as you walk forwards and backwards? (See diagram below for setup.)

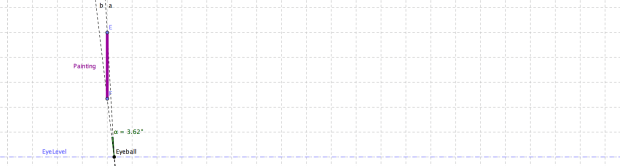

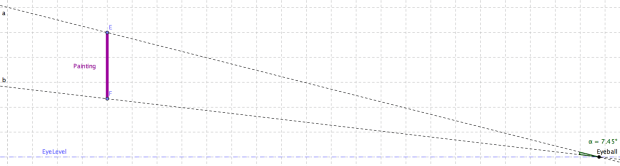

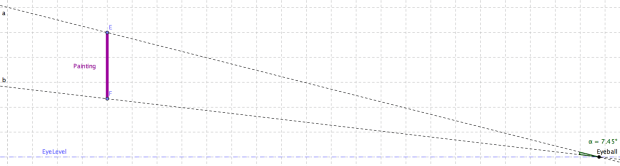

So to be clear, as you move the eyeball forward and backwards along the dashed blue line, what’s the largest angle you can create? Of course if you walk right up to the painting, or far away, the angle is going to decrease to 0. If you can’t see that, look at the diagrams below.

So of course there has to be some perfect distance that will give you the maximal angle. You see where this is going…

Find that maximum angle! (Use the variables in the diagram below.)

Of course this doesn’t have to be a painting. It could be, as the speaker pointed out, an overhead view of a hockey rink, with the painting being the goal, and the eyeball being the player with a puck. Where does the hockey player have the maximum angle to shoot and make it into the goal?

I want you to have the fun of solving it, but the solution I came up with was:

(I can help you with that if you want. Just throw your questions or cry for help in the comments.)

However, there is something pretty amazing about this problem, something that is powerfully seen with geometry software like geogebra or geometer’s sketchpad. Check out the sheet I made and see what happens as I bring the person close to the picture and look for the optimal angle? When you look at this, try to see if there is a geometry connection to our solution for the largest angle…

Vodpod videos no longer available.

Do you see the geometry connection? The optimal angle exists when the circle created by the top of the picture, the bottom of the picture, and the eyeball is tangent to the line of sight. Now my charge to you — which would be my charge to my students — is to (a) explain in words why this is true and (b) use geometry to calculate this optimal angle. You know, this work is an exercise for the reader. I mean, I’m not going to do everything for you. Sheesh.