The Water Cube in Beijing — you know, the one where swimming god Michael Phelps just broke all those world records? — has been touted in the media for being a very green building, capturing over 90% of the solar energy that hits it. However, in addition to looking cool, did you know that there is some incredibly deep mathematics behind the structure itself?

Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) was a prodigious and prolific nineteenth century thinker, and one of his interests was studying bubbles. (Seriously.) But to preface this post, take a moment and think about a single bubble. Why does it form a sphere — and not a cube or blob shape? The answer deals with forces and energy and the like, but the problem reduces to finding the figure with the smallest surface area for the amount of air contained in the bubble.

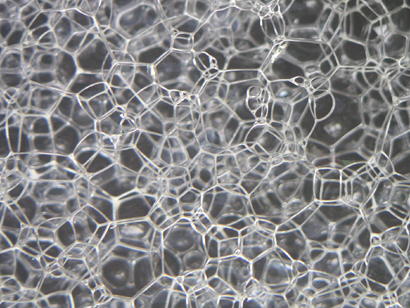

And if there are two bubbles touching, we know they meet and form a dyad of bubbles. And three bubbles meet, and they will always meet at 120 degrees. And more?

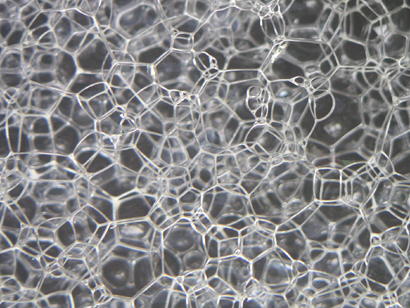

The more the bubbles, the more they are touched on different sides by other bubbles, forming flat faces. We end up seeing that the bubbles form polyhedra!

What if you had a whole bunch of bubbles in a foam bath? What would be the idea formation of them?

In 1887 Lord Kelvin asked the question: what is the shape that partitions space in such a way that the shape has the minimum surface area?

One example of a shape that partitions space would be boxes — stacking boxes, one on top of each other, in all directions. But boxes end up not having minimum surface area. Spheres aren’t a possible answer, because you can’t fill space with spheres — there will always be gaps between the spheres!

Bubbles, by their very nature, partition space by taking the shape that minimizes surface area. Kelvin studied bubbles and conjectured that the answer to his question was “tetrakaidecahedra.” Well, in his words, “a plane-faced isotropic tetrakaidecahedron.” (These are truncated octahedra.)

And in fact, there is a slight curvature, but “no shading could show satisfactorily the delicate curvature of the hexagonal faces.” But no worries, because you can see them yourself, like Kelvin did, by making a physical model:

it is shown beautifully, and illustrated in great perfection, by making a skeleton model of 36 wire arcs for the 36 edges of the complete figure, and dipping it in soap solution to fill the faces with film, which is easily done for all the faces but one. The curvature of the hexagonal film on the two sides of the plane of its six long diagonals is beautifully shown by reflected light.

I find it extraordinarily awesome that even though you can work on mathematics with pen and paper, you can play around and experiment with soap bubbles to see solutions.

It turns out that Kelvin’s conjecture was wrong. It wasn’t until 1993 that it was shown there was a better shape. Denis Weaire and Robert Phelan found shape that had 0.3% less surface area than Kelvin’s shape. To do this, they had to use a computer program!

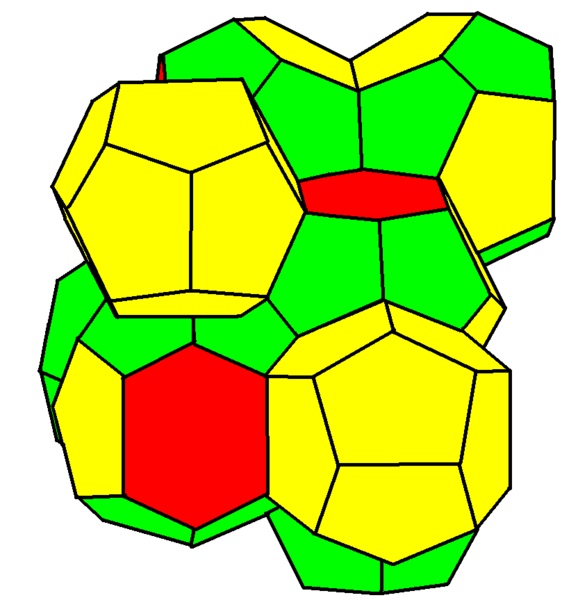

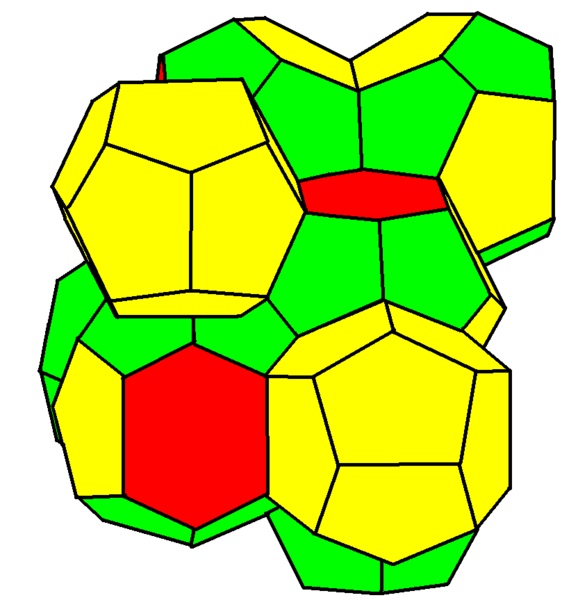

Their shape was more complicated looking. (Kelvin’s shape was formed from a single cell; Weaire and Phelan’s shape was formed from two different types of cells.)

If you want to build your own, you can print out the nets to fold here!

Wikipedia states:

The Weaire-Phelan structure uses two kinds of cells of equal volume; an irregular pentagonal dodecahedron and a tetrakaidecahedron with 2 hexagons and 12 pentagons, again with slightly curved faces…. It has not been proved that the Weaire-Phelan structure is optimal, but it is generally believed to be likely: the Kelvin problem is still open, but the Weaire-Phelan structure is conjectured to be the solution.

And this structure was the inspiration (and formed the basis) for the Water Cube in Beijing; we’ve come full circle. Surprising is the totally random look to the structure (like it had no order behind it). That was an effect achieved by taking a cube composed of the Weaire-Phelan structure, and then slicing it not horizontally, but at a 60 degree angle. See the excellent NYT graphics below.