So in multivariable calculus, it happens a lot. Most of the time, I can work things out and come back with a cogent response, and occasionally, I turn to you good folk. Today I was stumped, and then worked through it, and felt all proud of myself for about 60 minutes after I was able to figure things out. Here’s the set up and the problem:

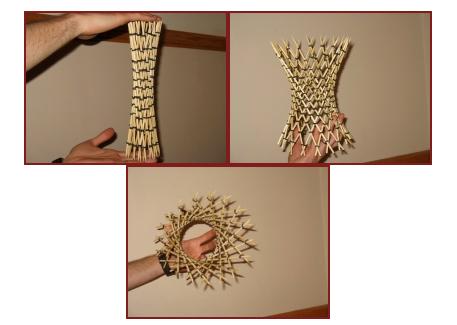

Today, I met with a student who is working on an awesome end-of-year project on center of masses. Basically, he’s making a bunch of semi-complex foam figures (with some other materials, like wooden dowels). He’s going to multivariable calculus to find the center of mass for these figures. Then he’s going to paint them black, mark the center of mass with neon orange, and toss them in the air while video taping it.

He was inspired to do so by this video I found online:

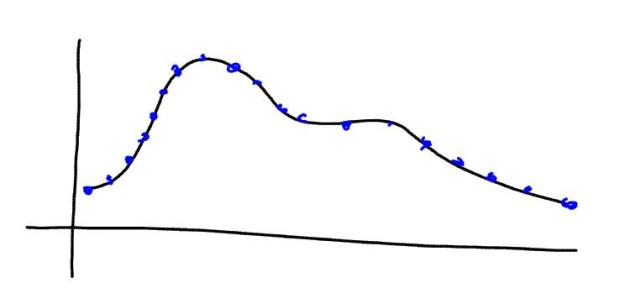

He’s going to throw the video he makes of his own crazy figures into LoggerPro (but Tracker would work just fine) and see if he gets a parabola.

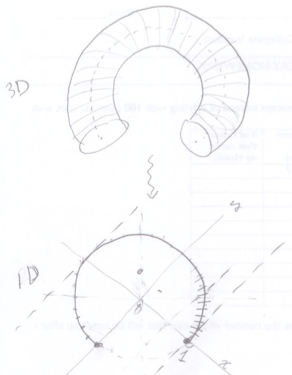

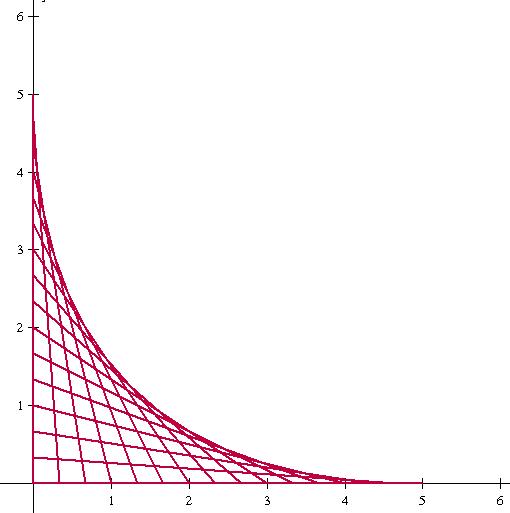

One of his objects is going to be something like 2/3 or 3/4 of a foam torus. He was having trouble finding the center of mass of it. The first thing we did was simplify the problem — changing the 3D foam figure of uniform density into a 1D bent wire of uniform density.

For the problem, we assumed 3/4 of a circular wire and we gave it a radius of 1.

Then the question was to find the center of mass for this thing. Clearly it won’t be on the wire [1], so you can think of it as such: if you wrapped the wire in super strong but super duper infinitely light saran wrap, and then you wanted to balance this wire+saran wrap figure on a pencil point, where would you place the pencil point?

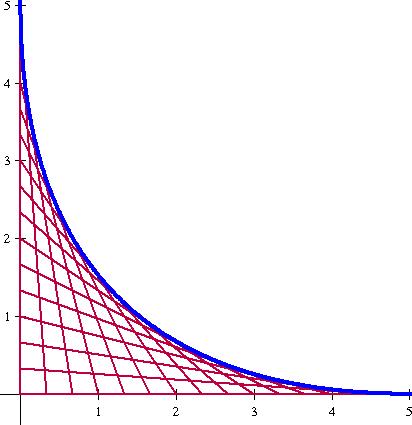

So I’ll admit that I struggled — but not as much as I anticipated. I started from first principles when solving the problem (cutting the wire into a finite number of pieces, and then making a Riemann Sum). And then this method allows me to find the center of mass no matter how much of the torus I have, whether it be 2/3 or 3/4 or e/pi.

I’m sure there’s an easy way to do this — much easier than reducing the problem to first principles and starting from scratch. But now that I have, I am pretty darn proud of myself. I think I understand the problem, now that I can look back at it, at a much deeper level. I can see symmetry arguments and how they come into play through the algebra, from working it out. I also can see how I can solve this sort of problem given any bent wire (any wire which I can describe parametrically, anyway). So yeah, I got a little bit… glowey.

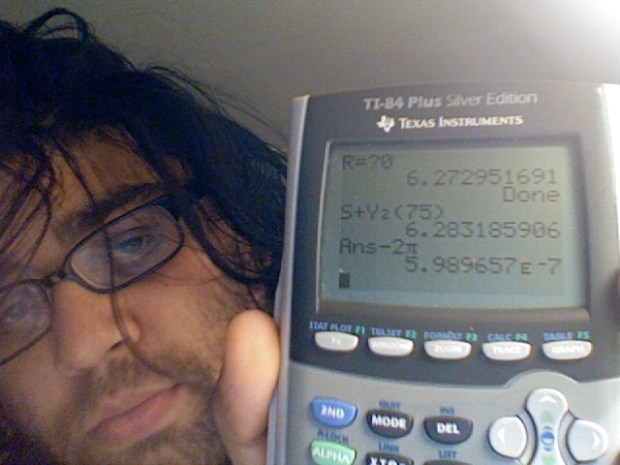

My favorite part of solving this (which involved discovering the error which confounded me for 5 minutes!) is when I ended up with:

Immediately I wanted to convert to

and have that cancel with the other

in the integral. That’s when I realized my huge mistake… after 5 minutes of hunting.

You can’t assume that . In fact, it equals

. And this small distinction makes all the difference in the world!

No, there isn’t any advice for you, and this isn’t about things I’m doing in my class, or even me fretting about how I’m not doing an amazing job. This blog also acts as a little digital archive, and I wanted to set aside this little glowey moment.

And if you’re wondering, I’m going to let my student sweat it out, and keep on working at it, until we next meet. If he hasn’t had that moment of insight yet, I’ll help him out.

PS. If you want to work out this problem or any variation, and come up with some beautiful and elegant solution (which y’all are oh so amazing at!!!), feel free to throw your thoughts/approaches/etc. in the comments.

[1] What he’s going to do, in order to throw it, is to put two or three light toothpicks in this partial torus, with a neon orange sticker attached to the toothpicks where the center of mass is calculated to be.