The math department, every year, gives awards to four students (some with some monetary compensation for college, some not). I was put in charge of thinking of some books to give with these awards. I sent my initial thoughts to my department head:

For the Math/Science award, I suggest:

*D’Arcy Thompson’s On Growth and Form is full of beautiful prose, and relates the sciences to mathematics. The actual science is wrong, but it is considered a classic piece of literature.

*Anthony Zee’s Fearful Symmetry about the important — crucial — role that mathematical symmetry plays in modern physics. A super-well written book for the layman.For all other awards, I put out there:

*Silvanus P. Thompson’s Calculus Made Easy has a deceptive title. And it was written in 1910. But almost all accounts agree it is one of the best textbooks around. Even for those who might have thought they understood the conceptual undergirdings of calculus, this book will illuminate them further, without any obtuseness.

*Douglas Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach is standard reading for all math lovers everywhere.

*Calvin C. Clawson’s Mathematical Mysteries is one of the best and most accessible popular math books I’ve read.

*G.H. Hardy’s A Mathematician’s Apology is quite good at explaining what a mathematician actually does philosophically when he works, written by one of the most important mathematicians of modern times.

My final recommendation differed slightly:

Award 1: Timothy Gowers’ The Princeton Companion to Mathematics

Award 2: Douglas Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach; Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; Bruce Hunt’s The Maxwellians; Silvanus P. Thompson’s Calculus Made Easy

Award 3 & 4: G.H. Hardy’s A Mathematician’s Apology

I really enjoyed thinking through which books might be appropriate. Also I didn’t want to give something I hadn’t read. But this process reminded me of all those books about math out there that I haven’t read (yet), but have really want to. Like Polya’s How to Solve It and David Foster Wallace’s Everything and More.

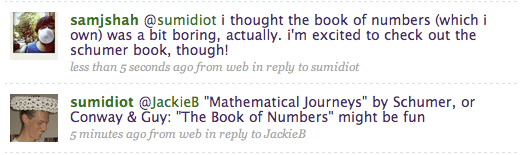

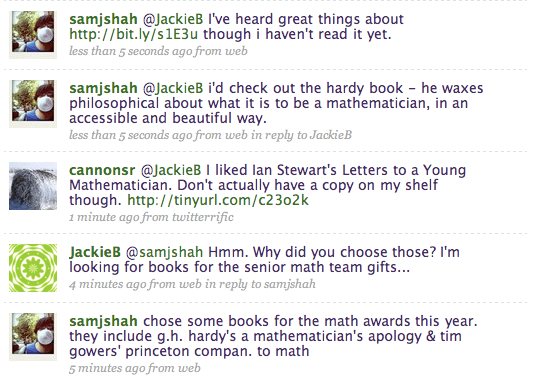

I posted this book award stuff on twitter, and got some great reactions. (Read from the bottom upwards.)

And then I thought: hey, you all must have a favorite math or math-y book that you’d want to have your favorite students read. I’d love to know your favorites! (Plus this list could help inspire me to do some quality reading this summer!)