Multivariable Calculus

Hyperbolic Paraboloid Inspiration

Inspired by a link from here, I just sent my multivariable calculus kids an email.

***

Hi all,

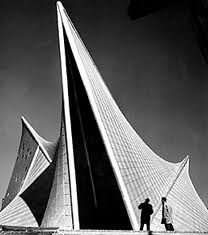

I ran across something so neat I wanted to share it with you immediatamente! Google the “Philips Pavilion” — either in regular Google or Google Images. A stunning building.

Also, a mathematical building. HELLO HYPERBOLIC PARABOLOID!

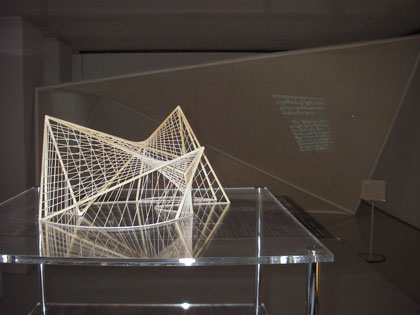

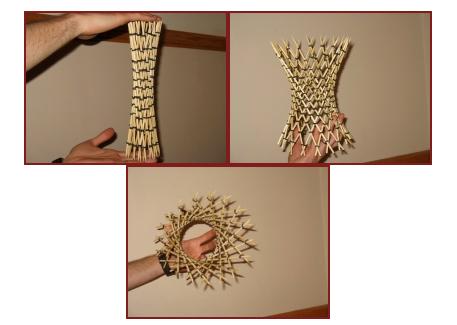

I love this model that someone, somewhere built. I mean, it’s simple enough that one of you could build it. And the best part is… You can talk about the math and PROVE that the mesh forms a hyperbolic paraboloid. Anyway, and idea for a final project.

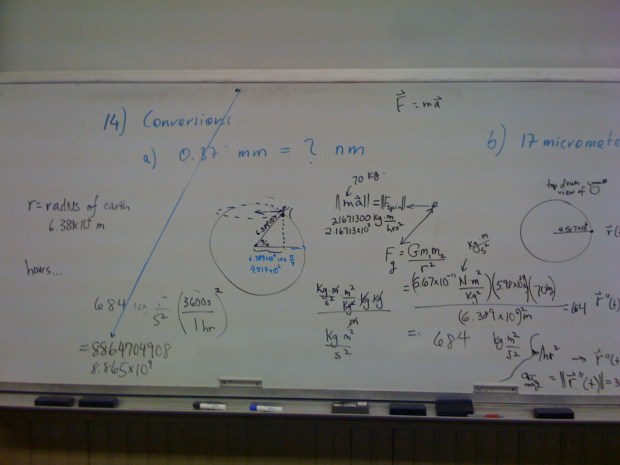

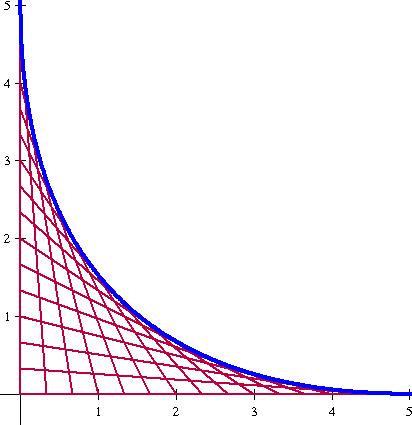

Last year I worked with Ms. TEACHER on a simpler problem — given this set of lines, what curve does this trace out:

In other words, what’s the equation of the blue line:

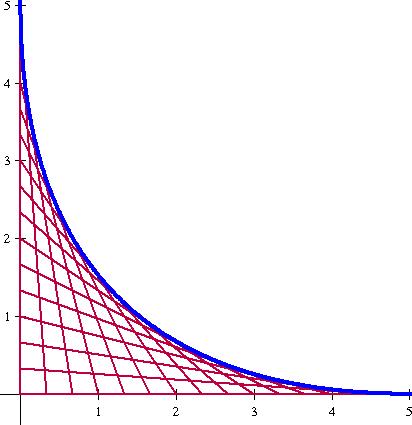

(In case you cared, we got using some nice calculus.)

In any case, I see this as the 3D extension to that problem.

So keep it in mind for your final project.

Best,

Mr. Shah

Riding a Flying Magical Unicorn

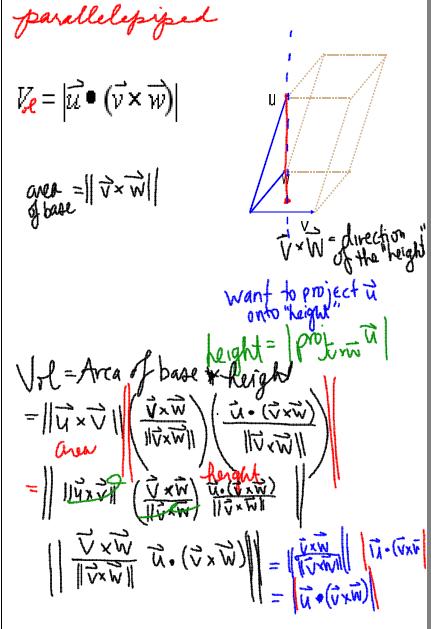

In multivariable calculus today, we were talking about the scalar triple product. It blows my mind that if you have three vectors:

, then you can show that the volume of the parallelepiped defined by them will be:

. And that if you expand this out, you get:

I mean, it makes sense that it’s symmetric in terms of — so that no one vector is privileged over another. But it still seems magical. I mean, even when I know that the determinant of a

matrix gives you the area of a parallelogram, it still seems so special that the determinant of a

matrix can give you the volume of a parallelepiped.

So we worked on proving that fact, with what we know about vectors.

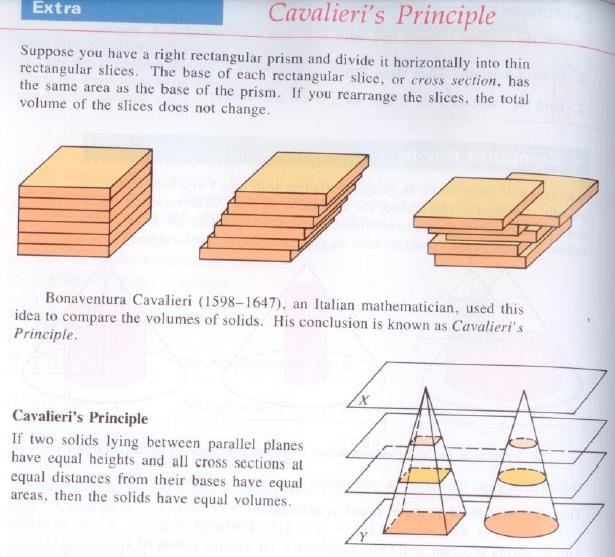

There are two hard parts to this proof. One is understanding that the volume of the parallelepiped is the same as the area of the base times the height. (And teasing out what the “height” actually meant.) At this point, I whipped out Cavalieri’s Principle.

It was in this discussion that one of my kids said the most awesome thing. When talking about Cavalieri’s Principle, he said: it’s like if you had 10 reams of paper all stacked up to make a cube. That has a certain volume. Then you push the stack so it leans — maybe so it’s a little curved. What’s the volume of the new stack of paper? The same.

So we understood what the “height” of the parallelepiped actually referred to.

The very last question: how do we find that? And in fact, my kids actually figured that part out without any help. They noticed it involved the projection of one vector onto another.

The rest? Just algebra.

It was lovely. And a different student exclaimed: “You should go around to the various precalculus classes, sharing that what you learn there actually will show up later in life!” (He was referring to vectors, determinants, and even parametric equations.)

Now to the title of this post. I was then transitioning to talking about straight lines in 3D. And I wanted to highlight that you just need a point and a vector to uniquely determine a line in 3D. Somehow, I got it in my head that I should explain it in metaphor. So…

I said that — suppose you are riding a horse. I mean unicorn. That can fly. But only in the direction of it’s horn. And you are told to go to a particular planet and wait there. At the starting gun, the magic, flying unicorn takes off, flying in the direction of its horn.

I am 99% sure this didn’t help kids “get” it. It was pretty obvious to them that a point and a direction (vector) uniquely determine a line. But I really enjoyed talking about the flying unicorn. I liked it enough that I think the flying unicorn may be our mascot for the year.

Plus, I like sparkles. And unicorns have sparkles coming out the…

A great Multivariable Calculus problem

Today I gave my multivariable calculus class a problem — a problem I give every year, that I found… somewhere. Maybe MIT, maybe an Exeter problem set, maybe a textbook. And if you ever want to see kids work together, and do some good problem solving, this is a prime problem for that.

Up to now, we’ve been working on vectors — and they learned vector basics (read: dot product and cross product). Here’s the question.

You have any tetrahedron. Sticking outwards from each face, orthogonal to each face, is a vector with magnitude equal to the area of face it is sticking out of. Prove that if you add these four vectors together, they sum to the zero vector.

It’s such a beautiful problem. I don’t have a totally geometric way to explain why this is true (we do lots of good vector algebra), but I do enjoy watching everything all come together. To me, it almost works like magic.

I then had a student ask an amazing extension question. (If they’re asking extension questions, you know it’s a rich problem.) He said: “Will this always work for any polyhedra? What about figures involving faces which aren’t triangles?” I, of course, decided I loved the problem. And I desperately want him to work on this for his final project.

I love the idea of this student taking this problem and seeing how far he can run with it. I mean: hello, gluing tetrahedrons together! (I expect him to make some stick models, if he does it!)

I love when kids stump me

So in multivariable calculus, it happens a lot. Most of the time, I can work things out and come back with a cogent response, and occasionally, I turn to you good folk. Today I was stumped, and then worked through it, and felt all proud of myself for about 60 minutes after I was able to figure things out. Here’s the set up and the problem:

Today, I met with a student who is working on an awesome end-of-year project on center of masses. Basically, he’s making a bunch of semi-complex foam figures (with some other materials, like wooden dowels). He’s going to multivariable calculus to find the center of mass for these figures. Then he’s going to paint them black, mark the center of mass with neon orange, and toss them in the air while video taping it.

He was inspired to do so by this video I found online:

He’s going to throw the video he makes of his own crazy figures into LoggerPro (but Tracker would work just fine) and see if he gets a parabola.

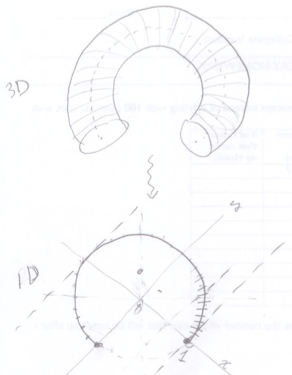

One of his objects is going to be something like 2/3 or 3/4 of a foam torus. He was having trouble finding the center of mass of it. The first thing we did was simplify the problem — changing the 3D foam figure of uniform density into a 1D bent wire of uniform density.

For the problem, we assumed 3/4 of a circular wire and we gave it a radius of 1.

Then the question was to find the center of mass for this thing. Clearly it won’t be on the wire [1], so you can think of it as such: if you wrapped the wire in super strong but super duper infinitely light saran wrap, and then you wanted to balance this wire+saran wrap figure on a pencil point, where would you place the pencil point?

So I’ll admit that I struggled — but not as much as I anticipated. I started from first principles when solving the problem (cutting the wire into a finite number of pieces, and then making a Riemann Sum). And then this method allows me to find the center of mass no matter how much of the torus I have, whether it be 2/3 or 3/4 or e/pi.

I’m sure there’s an easy way to do this — much easier than reducing the problem to first principles and starting from scratch. But now that I have, I am pretty darn proud of myself. I think I understand the problem, now that I can look back at it, at a much deeper level. I can see symmetry arguments and how they come into play through the algebra, from working it out. I also can see how I can solve this sort of problem given any bent wire (any wire which I can describe parametrically, anyway). So yeah, I got a little bit… glowey.

My favorite part of solving this (which involved discovering the error which confounded me for 5 minutes!) is when I ended up with:

Immediately I wanted to convert to

and have that cancel with the other

in the integral. That’s when I realized my huge mistake… after 5 minutes of hunting.

You can’t assume that . In fact, it equals

. And this small distinction makes all the difference in the world!

No, there isn’t any advice for you, and this isn’t about things I’m doing in my class, or even me fretting about how I’m not doing an amazing job. This blog also acts as a little digital archive, and I wanted to set aside this little glowey moment.

And if you’re wondering, I’m going to let my student sweat it out, and keep on working at it, until we next meet. If he hasn’t had that moment of insight yet, I’ll help him out.

PS. If you want to work out this problem or any variation, and come up with some beautiful and elegant solution (which y’all are oh so amazing at!!!), feel free to throw your thoughts/approaches/etc. in the comments.

[1] What he’s going to do, in order to throw it, is to put two or three light toothpicks in this partial torus, with a neon orange sticker attached to the toothpicks where the center of mass is calculated to be.

A good problem solving problem

So… I am in this “problem solving” group at school, and we spent today trying to come up with a lesson centered around problem solving that we could use for one of our classes.

I’ve been really hankering to make one of these hyperboloids out of skewers:

and I thought it would be a great investigation for my multivariable class to figure out if indeed that was a hyperboloid of one sheet. I figured it would take a number of days — at least one to create one of our own, and a good number to figure out how in the world we would come up with the equation to define that beast. [1]

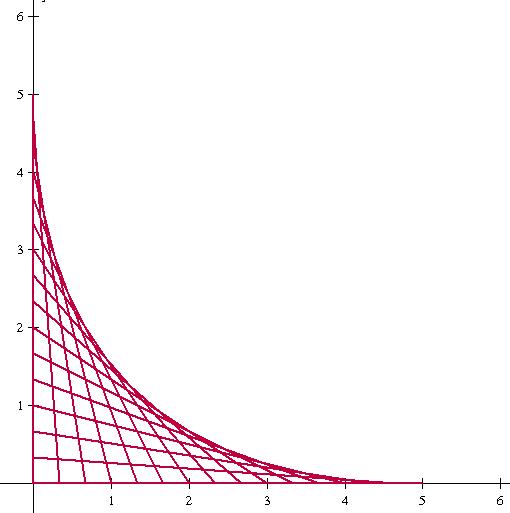

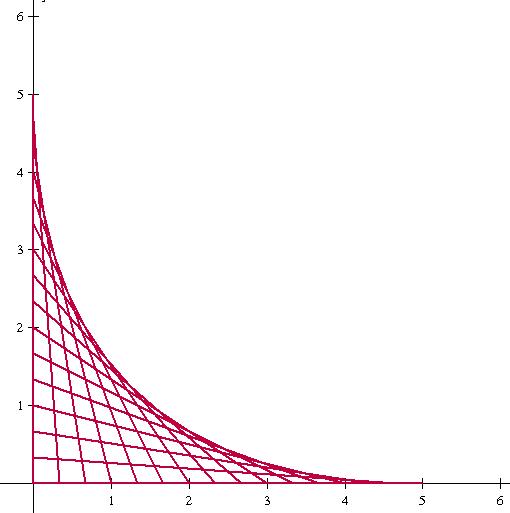

Of course one of the things we talked about in our problem solving group is how to bring the questions down to simpler questions — and then generalize. So I immediately thought of these drawings I spent hours of my childhood making:

[Yes, clearly my mother was happy that I found these to amuse myself with, instead of whiiiiiining “I’m so BORED… we have NOTHING to do in this house” as I did way too often.]

[Yes, clearly my mother was happy that I found these to amuse myself with, instead of whiiiiiining “I’m so BORED… we have NOTHING to do in this house” as I did way too often.]

If you look, they define a really nice gently sloping curve.

So my question is: what is the equation (written in terms of x and y) for the curve above?

The first segment goes from (0,5) to (0,0). Then another segment might go from (0,4) to (0,1). Another segment might go from (0,3.5) to (0,1.5). (So however much down you go on the y-axis, you go that much right on the x-axis.)

I haven’t solved the harder 3-d question yet, but I had a heck of a time solving this 2-d question.

Since I had so much fun, I thought I’d share the problem with you!

I’ll post my solution later, but if you want to throw your solution down in the comments and how you came up with it (or blog about it), awesome. Just like with this “circles, circles everywhere” problem where someone posted the most elegant solution EVAR.

Fourth Quarter in Multivariable Calculus

We’ve just started the fourth quarter of school, and I’m starting to see some of my kids slip away from me, getting farther and farther out to sea — little bobbing dots in the distance.

In multivariable calculus, I’ve designed the course to prevent that from happening. I have a serious fourth quarter project for them — totally designed and executed by them. (They have to make a prospectus, they come up with a concrete and reasonable timeline, they troubleshoot problems that arise, and they even come up with the grading rubric.)

But I do something else to change things up, which actually is pretty neat.

We watch videos.

These multivariable kids will soon be off to college and will likely take tough, lecture-based math classes, where you don’t get the individualized attention you get in high school. My kids have never been exposed to college lectures, have never learned to taking solid math lecture notes, and have never learned to work through the difficulties that the lectures might pose.

So in the fourth quarter, I teach about 1/3 of the final unit… and then I hand the class over to Denis Auroux of MIT. Yup, I download a bunch of MIT OpenCourseWare 18.02 lectures and we watch them together in class.

Today, we watched Lecture 19 on vector fields and line integrals in the plane.

After we get to harder lectures, we’ll get in the habit of spending a day watching a lecture, followed by spending a day going over questions, tying the lecture to the book, and doing problems.

I feel like part of me is lying to ’em, though, because Denis Auroux is such a clear expositor with amazing board technique. Not standard, by any means. (But why burst their bubble now?)

If you were teaching an AP Calculus course, I would definitely have my kids watch an 18.01 (single variable calculus) lecture at least a few times after the AP test.

PS. I should really show them something like this — which I got exposed two a few times as an undergrad. Not horrible, but you really have to be focused.