Each year, except for one, I’ve written a senior letter to deliver to my calculus classes (when I taught them) and my multivariable calculus classes at our last meeting. I pretty much always give the same sentiment — the life of the mind is important. I always crib a bit from previous years (the perils of being in a time crunch!). I wasn’t going to post it, because it is pretty much the same sentiment year after year. But this year, a student came up to me at prom and said that it meant a lot to him, and got him questioning a bit more about what his future might be. (Usually I hand it out and that’s it.)

So without further ado, this is my letter from this year.

***

May 27, 2016 – June 2, 2016

Dear STU,

It’s Friday evening, 9:53pm, and I’m at home listening to Kurt Cobain and his guitar. I know what you’re thinking, and sorry, nope: no showtunes today. Nearby is the book I just put down. It takes place in the nineties, the U.S. is entering a proto-grunge phase, and Nirvana is a recurring theme. The nineties is also when I was in high school and so every so often — usually when one chapter ends and I take a mental pause to regroup — I’ll get flashes of forgotten high school memories. You see, I have a terrible memory. It’s almost comical how much I don’t retain. Almost. So those moments where some feeling-rich memory is drudged up — the heart-pounding anticipation of a wildly-liked senior picking up friendless new-to-town sophomore-me in his car to go to a mock trial practice, or the awe of being perched on the roof of a house with a friend where every word carried into the night sky crackled with deeper meaning — I let them wash over me. Recalling them with any vividness get rarer and rarer as the years pass. (That’s something no one tells you about growing up. Your experience of the world dulls — from vibrant neons to faded pastel watercolor. Your memories become mottled with gaps, like a desiccated leaf chewed up by hungry pests.)

Why am I telling you this? As I now reminisce about me in the nineties, I know you are reminiscing about your lives too. Packer will become a temporary line on your resume, and then — soon into your working lives — not even that. (No one includes high school on their CVs.) You’re moving on, growing up, and you’re losing something and gaining something. You are adults and you are not adults. You are who you are and you are not (yet) who you are.

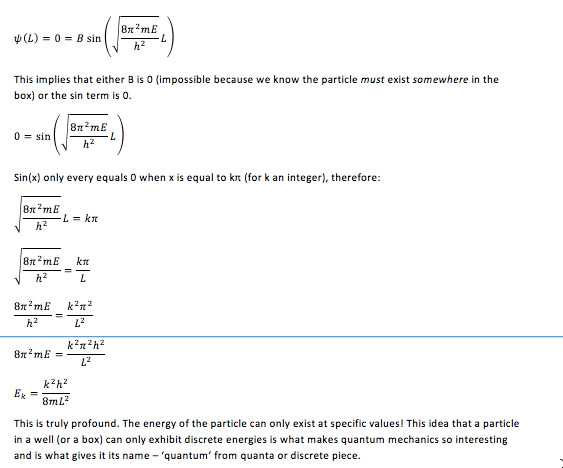

As you know, in physics there is a wave function. It’s a probability function describing all the possible states of some system. For example, is a particle here or there or waaaay over there? And — here’s the kicker — that wave function is the best that we can do to describe things. The system isn’t knowable in any better way. The function within it has all these possibilities, some more probable than others but still, oh so many possibilities. “How many?” I imagine asking you one day in S202, and in unison I hear you all replying “Infinite!” And left alone, the infinite possibilities undulate in time, directed by Schrodinger’s equation. Until one instant it isn’t. It collapses. All possibilities reduce to one actuality. Why? How? The why is easy: someone tries to find out more about the system… a measurement is taken. (A box is opened to peek at the cat.) And in that measurement the wave — and all the possibilities — is destroyed. (The cat is either alive or dead.) The how is harder: how does a collection of probabilistic states turn into a single state? That it happens is known, when it happens is known, but how it happens is unknown.

You — right now — are infinite possibilities spread out before you. Right now, you can’t even know what they all are, but they exist. The way you move through the world, the choices you make, the person you strive to be, those all shape the landscape of those possibilities over time.

Like you perhaps, I had grand designs when graduating high school. There were so many things I wanted to accomplish, so many things I wanted to learn. But one thing I did know — the thing that had the largest chance of becoming true — was that I wanted to become a high school math teacher. I truly never know if that nugget surprises students when I share it with them. I always think it does, because in my time at Packer, I’ve only had one student tell me they wanted to be a teacher (and now they are!). But here’s the thing: even then, I knew I loved math. Not in a small way, but in a way where I could work on problems for weeks and be in pure bliss. In a way that when I figured something out, I would force my poor mother listen to me outline how I cracked the mathematical nut — even though she had no idea what my excited explanations were all about. I wanted desperately to share with the world that feeling, of the frustrating and seemingly intractable journey ending in deep insight and a joyous satisfaction. I couldn’t not share that love with others! I wanted others to have that joyous satisfaction too.

I told my teachers this. And one — the one who looms larger and larger as I get further and further away from high school — got this about me. It was Mr. Parent, my junior and senior year English teacher. He occupies a special place in my limited memory because he was the first person I met who truly and fully embodied the life of the mind. The engine that drove this man was intellectual curiosity, and to bear witness to that sort of person – and his unbridled passion – had a lasting impact on me. At the end of my senior year I bought him a book and wrote him a letter explaining how much he meant to me. In that letter, I offered up a quotation by Richard Feynman, physicist and boyhood hero:

I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there.

If someone asked me what I wish for my students, I would answer with a pat: “to be good, and to be happy.” I can’t speak to being good part. That’s for you to figure out. But I suspect for you seven, because in you I see parts of me, one path to lasting happiness is to continuously follow your intellectual curiosity. That is our common bond, and one that I have been grateful to have had the opportunity to bear witness to from the first day of class until the very last day. Because we share that, I hope that you remember in the most bleak of days: there is something magical about the world around you. Keep an eye out for the magic. It appears as questions… and there are so many questions! How can we – billions of years later – know about the earliest moments of the universe? Where does matter come from? How can the world be probabilistic (quantum) in nature when everything feels so causal? How do we know about the smallest worlds we cannot even see? Why are there rainbows on the surface of an oil spill? How do rubber bands work – how do they come back to their original shape? How can we – on this planet – know how far things are, and that there are other galaxies out there? How is it that the natural world somehow can be encoded through simple and elegant mathematical formulas? Does that imply that math is somehow encoded in the universe, and it is being discovered rather than invented? Does the fact that we keep on digging in mathematics and are still drawing connections among disparate sub-fields imply that there is some grand unifying structure undergirding everything mathematical and physical?

Mr. Parent walked up to me on my graduation day and handed me a letter in return — a letter I treasure to this day, keeping it ensconced between the pages of my yearbook. In response to Feynman, he returned one of his own devising: “Stephen Hawking speaks of the thermodynamic, psychological, and cosmological arrows of time that define existence as entropic movement from past to future in an expanding universe. And that seems to define the hero’s journey: the personally expanding possibilities revealed in a courageous life bounded by and aware of entropic time.” I personally read this as an intellectual quest: you – dear students – are in a world that is growing in knowledge and is constantly reshaping itself around you. And you – dear students – have only a lifetime to enjoy it. And I mean “only a lifetime” because the world is vast and time runs short.

As you quest, don’t be afraid of failure. Let failure be a marker of pride, because you tried. You know me, I don’t know much about sportsing, but I do know that you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take. Set the bar slightly higher than you think you are capable of achieving and work extraordinarily hard. Harder than everyone else around you.

Wave functions collapse. But the possibilities of our lives only collapse when we are no more. You are an infinity of possibilities, remember that. You have so much time, and so little time. Make it meaningful.

Always my best, with sincerest best wishes,

Sameer Shah