I am exhilarated. The past two days in my calculus classes have taught me more about teaching (and more about student learning) than any other days this year. I am so engrossed in what’s going on that I feel like I might be at the brink of something big for my teaching… Maybe not, maybe this is just a passing thought, and I might grow bored of this, but right now it feels big. It could be a genesis for me-as-teacher.

As you know, I’m interested in the questions of how to teach problem solving, how to hone intuition, and how to build independence and tolerance for frustration for students. But on a whim, last week, I decided to temporarily throw all those huge questions out the window and just do something, anything, to get students to problem solve. My kids had just had a test on basic derivatives, so it was the perfect time to digress before Thanksgiving break.

So you know where we are… my calculus students had learned how to find derivatives of basic functions, they had learned the product and quotient rules, and they had a bunch of the conceptual ideas down. (For example, they could explain why the power rule works and where the formal definition of the derivative comes from.) But that was it. We focused on finding the derivatives of function after function after function.

So I gave myself 3 days to do something. I crafted a worksheet with 7 questions. Many just taken wholesale from our textbook, or slightly modified/scaffolded. I didn’t try to find hard problems. I have no interest in throwing my kids into the deep end of the pool [1]. Instead of “hard,” I tried to find problems that were different than any problems they had seen before.

You might look at this sheet and say “yeah, any calculus student who knows how to do derivatives ought to be able to do these questions.” But the first thing I learned in these two days is that that would be a huge mistake. In fact, it was a mistake I made for the past two years. I would assign one of these sorts of problems for homework, and the next day students would come in asking questions, and we would go over how to solve it in class. And by “we” I mean “I” would explain the solution asking students questions along the way. Then my kids would ostensibly know how to solve the problems. And I would move on, knowing they had “learned more calculus” and mastered “one more type of problem they might confront.” And although it may be true, my kids never really had to flex any of their intellectual muscles. They learned another algorithm. They didn’t ever have to struggle, minus a few minutes (seconds?) at home before giving up.

Here’s how these days went.

DAY ONE

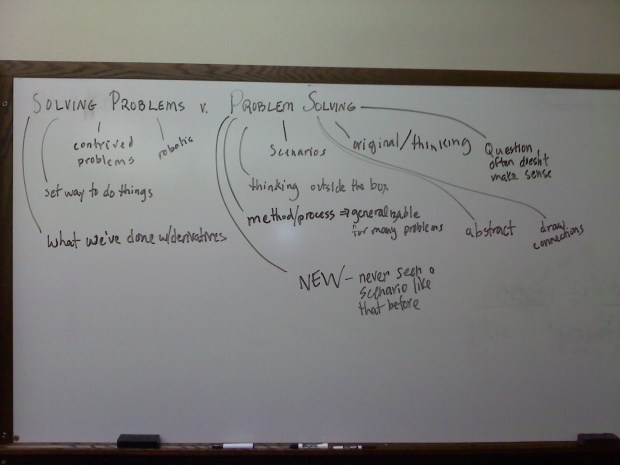

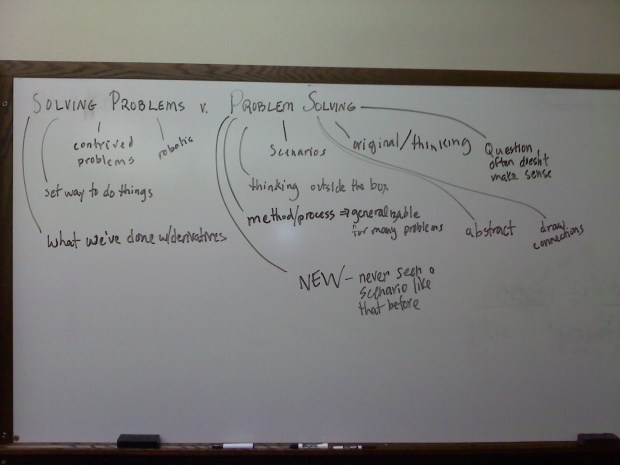

I start out with “SOLVING PROBLEMS v. PROBLEM SOLVING” on the board. I tell students what we’ve been doing in this unit is solving problems. I ask them what they think the difference between the two things are. This is what we come up with:

I put them in pairs. I tell some of the groups to work on problems 1, 3, 5, and 7, and the other groups to work on 2, 4, 6, and 7 — starting with whichever question strikes their fancy. I tell them that I won’t be of much use to them. That they are going to have to use their wit and wiles to do these problems. That they should ask their partners their questions, that if they really get stuck they should go to another group, and if they really, really get stuck, they can talk to me. Although I won’t be of much use to them.

They start working. For the remaining 40 minutes. They are totally on task. They are struggling to understand the questions, and they are trying to explain their ideas to each other. For example, for question 1, some groups just couldn’t understand what the question was asking.

Me: “Did you graph the two functions like the problem said?”

Them: “No.”

Me: “Maybe that will help you understand the question.”

[I come back later]

Me: “Do you understand the question now?”

Or sometimes I would get some student needing affirmation:

Them: “Mr. Shah, for this problem I first took the derivatives of the functions and set them equal to each other and then I solved and got this quadratic and then since I couldn’t factor it I used the quadratic formula.”

Me: “That sounds like a statement. Do you have a question?”

Them: “Well, I guess I’m asking you if I’m on the right track.”

Me: “You know I won’t answer that. Do you think you’re on the right track?”

Them: “I think so.”

Me: “So go with it. Stop worrying about being right at every step. Have confidence. Talk things out. Make mistakes. Whatever. Now stop bothering me.”

I have to encourage a couple of people to work as a team instead of independently, but other than that, my students are killing it. It is amazing. I can’t understand what it is, but my kids are really into this!

One of the groups which is working on problem 4 says “Mr. Shah, now that we’ve done part (a) and part (b) for this question, we’re not problem solving anymore. We’re just solving problems when we’re doing part (c).” I almost cry. My kids are starting to recognize on their own that once they problem solve and get a technique down, they are then only solving problems. They have another tool in their toolbelt with which to problem solve.

At the end of the class, I say “Stop.” Most have only solved 2 or 2.5 questions. I smile and tell them that’s alright, and that they are doing so amazingly that I am not going to assign any homework.

Lessons from DAY ONE:

- The “easy” questions I chose aren’t so easy, since my kids have never seen questions of that particular form before. As I suspected, this is problem solving for them.

- The kids who are afflicted by “learned helplessness” (read: who always raise their hand at the first sign of trouble) can think for themselves. In other words, my kids can be independent thinkers if forced to.

- Kids need time to struggle and grapple and do basic things like draw parabolas and hyperbolas. I assume they can do these things quickly. They can’t.

- My kids are not to be underestimated. I realized that I regularly underestimate the ability of my kids to think for themselves. Which is one of the biggest reasons it has been hard for me to let go of my teacher-centered class, and lead more of a student-directed class.

- Many of my kids actually found math fun/interesting! Without the stress of grades and time pressure, they got to enjoy the puzzle aspect of math!

I sent out a survey to my students asking them about this first day of problem solving.

Some of their positive responses (and see this teaser post for my favorite response):

It’s exciting to think that we are finally able to combine a lot of the formulas and other material we learned previously to solve a single problem.

I think it went well. It was tough, but rewarding to get an answer, even though we still weren’t sure if it was correct.

I found the class really interesting because I often find myself neglecting my brain and just accepting what teachers tell me. It’s a nice change of pace to think for myself for once and truly try to understand it.What makes me excited about doing more of this is that I feel the more we do, the more comfortable we will be with doing them.

I think it went really well, actually. I liked the problem solving.

I liked doing problem solving because it was different from what we’re usually doing. It’s also a good way to work on a different way of thinking about things, which I’m always appreciative of.

I think it went well. It’s hard to start out a problem, but then at a certain point things start to click.

It wasn’t bad, it was good working in groups so that we can bounce ideas off of each other. It was good applying the things we learned previously.

Im excited to be able to do harder problems, and it makes the easier problems look and feel alot easier.

It’s really interesting and challenging. Solving these problems is like solving puzzles because you already have the pieces, but you need to find a way to piece them together so they form a whole.

I like working with a partner on problems. i think that these problems feel very comprehensive which is fun.

There were no negative responses. There were anxieties though. All of their anxieties about problem solving boiled down to two things: grades and their ability to actually do the problems since there is no set method to solving them.

DAY TWO

I start out the class reminding the kids about problem solving. I talk about their survey responses, and the anxiety about grades. I tell them to mitigate their fears, whenever we problem solve I will always give them a choice of problems to work on, I will let them work in pairs (at least for now) so they can bounce around ideas, and that I will grade them on more than just answers. I will grade them on their formal writeups and the clarity with which they explain their approaches to the problems, even if none of their approaches succeeded. My kids seemed to feel those addressed their concerns.

I set them off to work with their same partners. If they worked on the even problems, they should work on the odd problems (regardless of whether they solved all their even problems). If they worked on the odd problems, they should work on the even problems (regardless of whether they solved all their odd problems). The students work. I wasn’t sure if they’d still be into it, but they are.

Five minutes before class ends, I stop everyone. Most groups had gotten 3 more problems done. I tell everyone their homework. Each student must pick two problems and do a formal writeup for those two problems. No one in the group can do a formal writeup of the same problems, though. I ask them how day two went. They agreed that it was (on the whole) much easier the second day, now that they knew what they were doing and how to work with their partners.

Lessons from Day Two

- I suspect that two days of problem solving is enough. I think more time will make what we’re doing into a chore instead of something new and exciting.

- My kids really, really want to know if their answers are right. I refuse to tell them. That bothers them. I tell them that’s part of problem solving. And then I asked them if they have a way to check their answers themselves?

Where am I going from here?

1. Tomorrow, I’m going to have each student exchange their writeups with their partners. They are going to read through the writeups, and come up with comments and suggestions for clarity. Diagram here? Explanation there? After 15 minutes of discussion, I’m going to tell them that the remainder of their classtime will be spent writing up a better version of their partner’s solutions. Their final draft. Which will be graded.

2. Now that my kids have struggled with some easier problems, and know they are capable of working them, I created a bunch of harder problems. I am going to distribute these problems to my classes, partner them up, and give them one week and two weekends to solve 2 of the problems. I will give them 20 minutes to work together in class in the middle of the week. The problems are here, if you want to see them.

3. I’m going to photocopy each classes’ writeups and distribute them. We’ll talk about what makes a good writeup and what makes a bad writeup.

4. I think I might spend two days after each unit doing this.

And with that, I’m out.

[1] One thing I want to avoid at all costs is being one of those teachers who says “I teach problem solving” while actually just giving hard problems to kids and then watching them struggle. I want to teach problem solving. That’s tough.

is the same as

, and my calculus students still don’t know why

, and I’ll remember why I have such a singular focus on understanding, jettisoning fun for more immediate concerns.