At the end of the past summer (oh how long ago that was! glorious days of freedom!), I hunkered down at a coffeeshop with @jacehan in preparation for this school year. I was fixing up some of the things we did last year in geometry. One thing I wasn’t pleased with was how we taught the crossed chord theorem…

So I created a totally new approach. Instead of having students discover the theorem, I would work backwards. Here is the TL;DR from my last post — after I had created the activity.

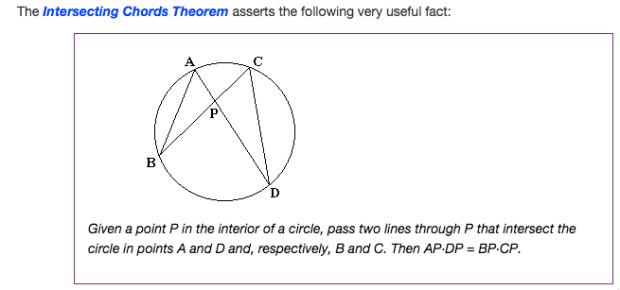

The TL;DR version: students investigate all quadrilaterals where the diagonals satisfy the property that ac=bd. Students are guided to make a conjecture which we as teachers know will be wrong. Then we show a counter-example to blow their conjecture up. And them bam: they have to try again. Using geogebra and some more encouragement, students discover that all cyclic quadrilaterals satisfy ac=bd. And so the circle emerges out of this investigation of quadrilaterals and diagonals. This is, then, the crossed chord theorem. Which students got at by investigating quadrilaterals. Weird. Now they are in a prime place for wondering why the circle shows up. Proof time!

When I shared the activity, I got a couple suggestions from @k8nowak and @bowenkerins and so I modified it with a single tweak which made it oh so much more powerful. In this post, I will talk about my experience implementing the activity, as well as share the modification I made. However I entreat you to read the original post as I’m not going to outline everything again! So go read! Okay? Okay.

(1) First off, the change. I made a change to the very last question on the sheet… Instead of having students look for blermions “in the wild,” I had them fix three points and find a bunch of different locations for the fourth point (so the quadrilateral would be a blermion).

[docx: 01 Crossed Diagonals [new]]

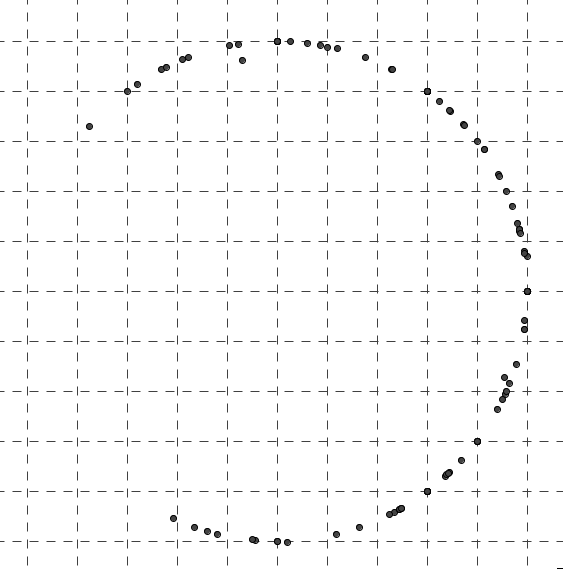

At the end of class, I had students fill out a google form with their possible fourth points location.

(2) In class, when students were filling out the conjecture in #4, I saw a number of interesting conversations happening. Their conjectures were essentially: (a) all blermions need at least one pair of parallel sides, (b) all blermions have supplementary adjacent angles, and (c) a blermion has opposite angles supplementary. Most students didn’t find any kites that were blermions, which is why they came up with conjectures (a) and (b). But when the few students who found blermion kites said this to the class, we realized that (a) and (b) couldn’t hold anymore. But conjecture (c) was a possibility still.

Now to be clear, I was expecting conjectures (a) and (b). I was floored when not one but two groups out of five wanted to persevere and find a good conjecture, and used geogebra to measure angles. It was awesome. And it led to a great discussion later on. More on that later.

(3) I asked kids why I had put question #5 on the sheet… what might have been my motivation? I liked asking that question and having groups discuss, because they all recognized that by only looking at “nice” shapes (which, granted, I asked them to do), they could only make limited conjectures. And as soon as they see the blermion in #5, most conjectures would go out the window. The point? To show students that all quadrilaterals aren’t “nice.”

(4) The moment when students saw all their group’s data together in #6… Well, two of my groups got to this point in class. It was … incredible. Kids had their minds blown. Something totally unexpected happened.

For the other groups, I shared the class data (from the data they entered in the spreadsheet):

Holy cow! It is so beautiful! All possible fourth points of a blermion seem to lie on a circle!

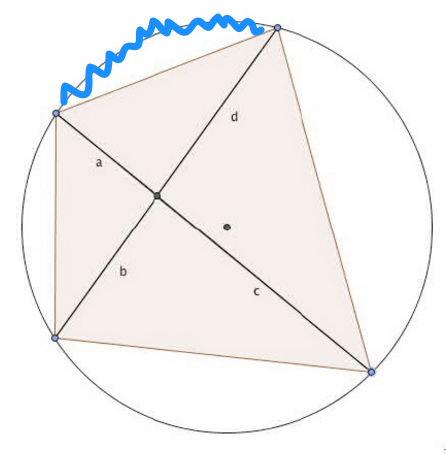

(5) Students then wrote a conjecture, and we said if the conjecture were true, we’d suspect (from the Always Sometimes Never questions in #3) that all squares, rectangles, and isosceles trapezoids could be inscribed in a circle. And we discussed how we were going to prove the opposite: If you have a cyclic quadrilateral (yes, I introduced that term!), that product theorem thingie (a)(c)=(b)(d) holds with the diagonals. Okay, we were a bit more formal, but that was the crux of things.

(6) Before proving that, I wanted to exploit the conjecture (c). I had students prove that all cyclic quadrilaterals had opposite angles that were supplementary. They struggled a bit with this, but once they had their insight, BOOM. (They used the inscribed-central angle theorem thingie — a central angle is half its corresponding inscribed angle).

(7) Then I left students to prove the crossed chord theorem. I gave them this sheet:

[docx: 01 Crossed Diagonals (proof)]

Almost all kids got to the point where they recognized two pairs of similar triangles. And they recognized that if they could prove one pair of similar triangles were congruent, they could set up a proportion and be done! But the problem was proving the triangles similar. Almost all groups got stuck here — and even though I said: you’re almost there! Think about the inscribed-central angle theorem! — they couldn’t progress. I didn’t do a great job of knowing what to say next.

What I did was show them this (which they had created earlier). For some reason, this did not work for them as a hint.

In the future, what I should do is just highlight an arc for them… and say “this arc can guide you!”

Maybe that will work better?

However, eventually all groups got the proof.

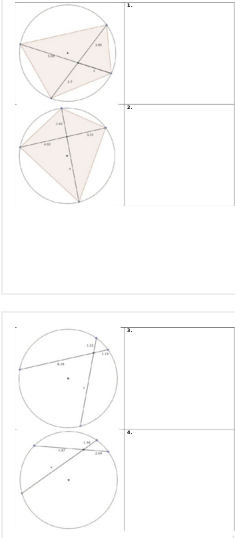

(8) At this point, I had students start solving problems. Two with quadrilaterals and two with chords.

Again, I asked them why I included had the second two types of questions, and had the discuss in groups. They recognized that the theorem didn’t need to be stated with cyclic quadrilaterals… Instead it held if we are talking about two line segments in a circle (at that point, I introduced and defined the terminology “chord”). Then I had students write the theorem we had proven without reference to the quadrilateral, and we went around and shared and critiqued the wording.

***

I don’t always love the stuff I come up with. Sometimes it flops. Sometimes it’s pretty good. But rarely do I think it’s so awesome that I would give it the stamp of “highly recommended.” This gets that from me. It is interactive, there is a moment when kids’s minds are blown, and it ties together so many interesting ideas.

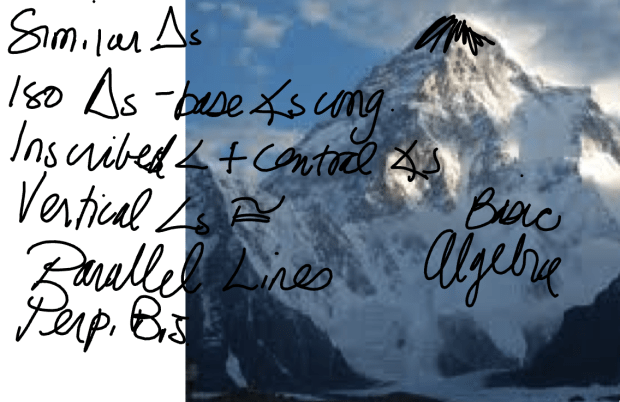

For context, I did this after we did our unit on similarity. We then proved that the base angles of isosceles triangles were congruent. We then used that to prove the inscribed-central angle conjecture (download here: A Conjecture about Inscribed Angles). And then this. It flows so nicely.

***

Yesterday, as we were wrapping this all up, I said to my kids:

“This thing we just proved about circles and chords… this is at the top of a mountain… this theorem is based on lots and lots of other things. If I gave you a bunch of circles with two intersecting chords in it at the beginning of the year, and said, give me some conjectures about this, I doubt you would ever have stumbled upon this… or if you did, it would have taken you a long time and it would have been an accidental discovery. You still wouldn’t have known why it was true. But now you have built so much mathematics throughout the year that this wasn’t an insurmountable feat. What ideas did this theorem lie on?”

And we even had more. We had to know a lot to get there. But wow, it might have seemed impossible at the start of the year, but it was totally doable with all the tools we’ve put in our toolbelts. And how wonderful and inspirational is that?!

Update: Here is a post about an extension I did on this — involving merblions.