Today was exhausting. It’s been a while since I really, really planned for classes. The past week was this weird interim week where I didn’t work full-force. Midterms were canceled and classes continued, but in this half-hearted way. So it’s been a bit of a shock to sit down and plan 3 lessons, and do a giant pile of grading.

I counted. Today I graded 216 papers, which consisted of 600 problems (not counting parts a, b, and c as separate problems). I created 57 SmartBoard slides (well, some I cribbed from last year, or from previous classes). I entered 24 grades in my gradebook. I modified and printed one worksheet on the quadratic formula. I created my next problem set for my Multivariable Calculus class [1]. I set up my calendar for the next two weeks. Go me!

The next week is going to be brutal — the start of a new quarter, along with the task of entering and finalizing all the grades from the previous quarter.

I’m actually nervous about this upcoming week — but not only because of the work I’m going to have to do. Because of the student death at my school, two weeks ago, everything has been in disarray. Midterms were canceled, tests were modified to be open note or take home, movies were shown in classes (including some of mine), and students were given lots of flexibility. (“You were unable to focus last night? Of course you can take the quiz in study hall tomorrow.”) In other words, for the past two weeks, I unclenched my fist. My expectations were blurred. They were also greatly lowered. Starting tomorrow, I have to go through the process of re-clenching my fist. It’s going to be hard. I’m going to be clear with everyone that even though we’re not going to be the same, life has to go on in my classes. We’re going to go full force, and I am going to have the same high expectations for everyone that I had earlier in the year.

Here’s to hoping that the transition will go easily. I believe that as long as I’m clear with them, they’ll rise to the occasion. They have in the past.

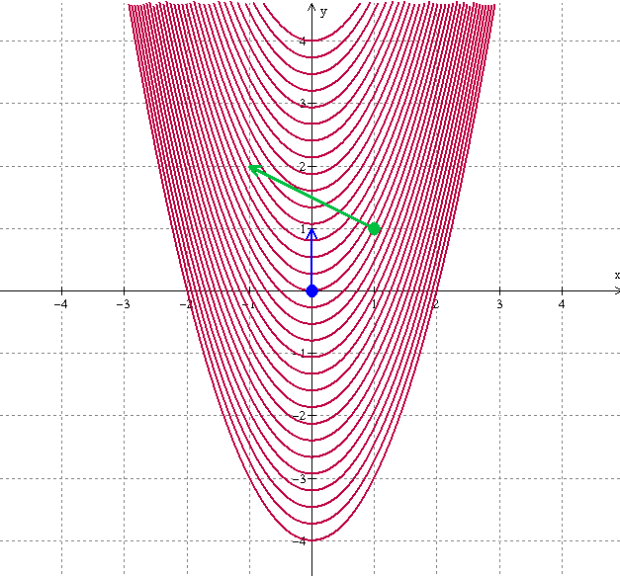

[1] Actually, this problem set is going to be different from the others, and I’m hoping pretty interesting. I am assigning them one problem on using multivariable calculus to find the line of best fit (some of them are concurrently taking statistics), and then they are asked to create their own problem set for the material we’ve covered. Three problems. One which they have to make up themselves, but they can be inspired from any resources. The other two can come from other resources. Heck, you can read the problem set here. I’m hoping that having them dig for problems that seem interesting to them will keep them excited about the material. I’ll let you know how that goes.

In fact, here are all my problem sets so far.

multivariable-calculus-problem-grading-rubric

problem_set_1a

problem_set_1b

problem_set_2a

problem_set_2b

problem_set_3a

problem_set_3b